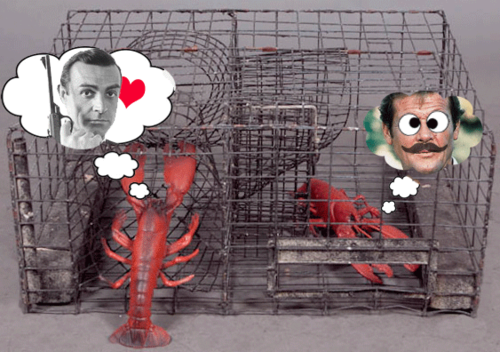

Everyone has a favorite James Bond actor. Typically, the Bond that ushers us through childhood earns a special place in our hearts and minds. If you didn’t grow up with Bond or came to the movies later in life, sentimentality might play a smaller role. And with or without sentimentality, there’s still the risk of falling blindly into the Connery lobster trap whereby one blindly argues that Bond is Connery and Connery is Bond and thus the conversation is done.

Did he just smack-talk Sean Connery’s Bond a little bit?

Yes, but don’t read too much into that. Sean Connery defined the role, a Cro-Magnon womanizer with a million-dollar smile. His portrayal of the character has influenced every other actor that has donned the tuxedo. But we’ve got to be honest with Connery’s legacy as 007. Terence Young, the director of Dr. No had as much to do with the creation of cinematic James Bond as Sean Connery. The late Lois Maxwell (Moneypenny) said, “Terence took Sean under his wing. He took him to dinner, showed him how to walk, how to talk, even how to eat.” Young even outfitted Connery in his Saville Row suits. He taught him how to talk without gesturing with his hands. Other members of the production team have remarked that Connery was just doing a Terence Young impersonation. It is also said that Young likely modeled Bond on the lifestyle of Eddie Chapman, a wartime double agent (codenamed “Zigzag”) who had been a friend of Young’s before the war. Young molded Connery into James Bond, like a piece of unformed clay.

Connery only made two objectively great Bond films and, upon his ultimate departure (the second time), left the series in uncertain shambles. His growing disinterest in the role seeped onto the screen in You Only Live Twice, and after a short hiatus, EON and United Artists (in full panic mode) turned around and rewarded him with a then preposterous salary of $1.25 million plus 12.5% of the film’s profits (and the promise to financially back two subsequent non-Bond movies of his choosing) to star in Diamonds Are Forever. It should be noted that Connery’s paycheck went towards funding childhood arts programs in his native Scotland; I do not intend to paint him as a financial glutton. While it would be impossible to pin the quality (or lack thereof) of that film on Connery alone, he does not tackle the role with the gusto that made Bond a success. Then, years after promising he’d never play Bond again (suggesting he’d outgrown the role), he turned around and took another huge paycheck to make Never Say Never Again (a remake of Thunderball) with EON’s longtime nemesis Kevin McClory.

Time for a grand generalization. The same Bond fans that overlook Connery’s missteps also seem to irrationally denigrate every other actor to have played Bond. Their tunnel vision feeds the cult of “The One True Bond.” While Dalton takes his share of bludgeoning, he only starred in two films and neither of them were named Moonraker. Nay, one Bond in particular takes the lion’s share of scapegoating for everything wrong with the post-Connery era. That Bond’s name is, of course, Roger Moore.

But Roger Moore ruined Bond for more than a decade! He’s doing Bond wrong!

And it’s easy to think that. This popular opinion infects the minds of fans who see only the best in Connery and focus on the worst of Moore. I’m going to lay something down here that might confuse some people. If you’re in the lobster trap, you might need to brace yourself. Without Roger Moore, James Bond doesn’t survive. Sean Connery and Terence Young may have invented cinematic James Bond, but Roger Moore shepherded the character through the valley of the shadow of the cynical 1970’s.

As I mentioned in my rumination on Live and Let Die, a primary component of 1970’s culture was disenfranchisement. Compound this disenfranchisement with the Bond formula having been stripped down to its skivvies as a result of the parodies, imitators and cultural deconstructionists who had deemed James Bond a relic from a bygone era. The movement toward gritty cinematic realism that reflected the loss of our collective rose-colored glasses left Bond in limbo. Diamonds Are Forever and Live and Let Die had both tried to merge the worlds of “gritty realism” and James Bond escapism with limited success. Clearly, the era of Connery’s brutish, sincere womanizing had passed, but Broccoli and Saltzman were determined to march on, staunch believers in the longevity of the James Bond character despite critical disapproval.

Selections from reviews of Live and Let Die:

Bond slips unobserved from one hiding place to another; is discovered; eludes his pursuers; watches as six hired goons hurry past; and then goes through another door and unexpectedly finds the villain waiting there for him. The dialog here is always the same, something like “Come in, Mr. Bond, we’ve been expecting you . . .” And then . . . but do you get the same notion I do, that after nine of these we’ve just about had enough?

-Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times

There is a new James Bond — Roger Moore of Sainted TV memory — and a new angle to his latest adventure. In this incarnation, 007 is the Great White Hope. He goes about beating up black men who are doing a little heroin smuggling to finance a Caribbean dictatorship and, perhaps, take over the U.S. after they’ve turned it into a nation of junkies with their free-sample program. Both novelties are deplorable, and Live and Let Die is the most vulgar addition to a series that has long since outlived its brief historical moment — if not, alas, its profitability.

–Richard Schickel, Time Magazine

James Bond movies live and die with the charisma of the actor playing 007. With the exception of perhaps Die Another Day (which repulses for many reasons that have nothing to do with the dedication of Pierce Brosnan), even bad Bond movies are made watchable by the actor’s ability to buy into the relative nonsense. It should come as no surprise that most of what happens in James Bond movies trades on “the improbable.” Individual Bond films readjust the balance of “the improbable” and “the real” according to cinematic trends and particular plotlines. As EON tried to determine how best to steer Bond through the uncertain early 1970’s, Bond films vacillated wildly between “the real” and “the improbable.” In Diamonds Are Forever, Live and Let Die and The Man with the Golden Gun, the filmmakers couldn’t decide whether to stick to the their initial impulse that had created On Her Majesty’s Secret Service or foreground the more fantastical elements that had always been present. The entire formula, however, was thrown into flux as Bond chased the new, cynical future.

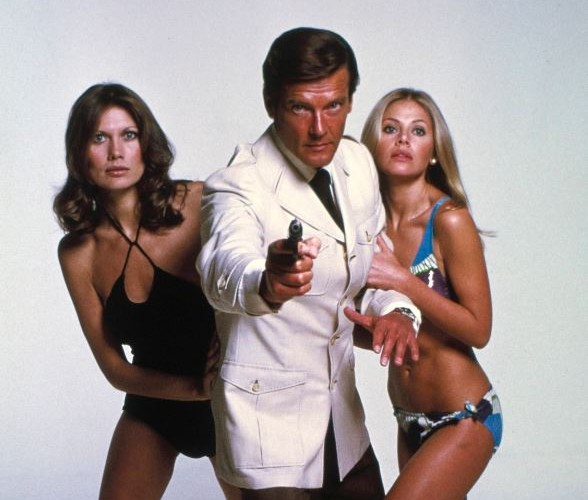

With the casting of Roger Moore, EON committed to a new tact. Moore wasn’t a brass knuckle like Connery or Lazenby. He was a debonair playboy, “a cunning linguist” (to borrow a quip from Tomorrow Never Dies) who wooed with words and delivered one-liners with panache. Moore played James Bond like a trust-fund man-child who chased women and danger for sport. A matter of entitlement separates the images of the two Bonds. Women fell at the feet of Connery’s Bond with just a glance; the women in Moore’s movies, too, ultimately fell into his arms with uncontrollable desire, but Moore had to expend some effort to woo them first. It’s a subtle difference (because the amount of wooing Moore had to perform was often minimal) but one directly influenced by the progressive 70’s and the post-feminist movement.

What difference does that all make? Moore’s movies were still terrible.

But “terrible” by who’s standards? I would argue that both Live and Let Die and The Man with the Golden Gun better serve the franchise than the self-parodic You Only Live Twice or the dismal Diamonds Are Forever. In fact, the latter more appropriately reflects the criticisms of the Moore movies than the reality of the Moore movies themselves. Vapid. Quippy. Smarmy. Choose your own adjective; they’re all contained within Diamonds. Those first two Moore movies reflect a rudderless Bond searching for relevance and desperately trying to connect with a new breed of audience. They’re a mishmash of popular culture with no particular consistency. They’re also each half-steps back to a proper James Bond character and cinematic adventure, perhaps not the traditional Bond created by Connery and Young… and certainly not the product of the overidentified demi-god raised to the heavens by the Connery loyalists.

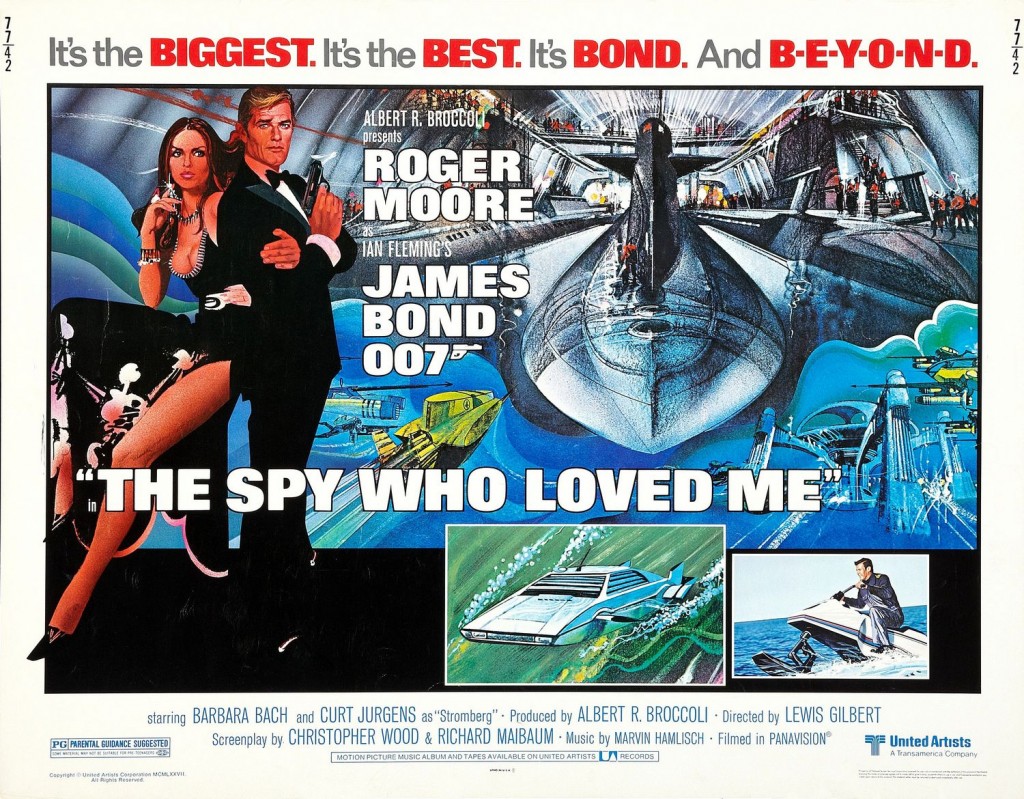

Break down the basic building blocks of the Bond formula. Dapper and worldly secret agent. Beautiful (and intermittently capable) women. A megalomaniacal villain with an elaborate scheme. A feared henchman. Spectacle and fetish delivered through sex and action, flashy vehicles and the broad scope and scale of danger. Even on paper The Spy Who Loved Me fits each of these criteria more perfectly than perhaps any other Bond movie that had come before it. Yes, including each and every movie starring Sean Connery. Whereas You Only Live Twice quilted each of these elements into a disingenuous and artificially crude tapestry, The Spy Who Loved Me is perhaps the most seamless collection of traditional James Bond elements. The most interesting Bond movies are often ones that challenge the Bond formula without undermining it. Look at how Skyfall and On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, in particular, play with audience expectations – both excellent films. But I propose that the most viscerally thrilling Bond adventures take place when the formula is adapted and tailored to contemporary tastes and the strengths of the character playing Bond, no strings attached. The success of the James Bond films relies on pure escapism. Thus, I submit The Spy Who Loved Me as escapist Bond par excellence.

Ugh, you’re still on this Roger Moore thing? How can there be this much to say about all seven Roger Moore movies, let alone just one?!?

Andrew Pulver on the Guardian website writes:

At the time, the film certainly made an impression. Everything about Bond movies – Barbara Bach’s cheekbones to the underwater harpoon battles – seems calibrated to appeal to the adolescent. Now older and wiser, I like the self-parody that Roger Moore brought to the role; I always found the “serious” Bonds – Connery, Lazenby, Dalton – out of kilter with the hyper-absurd environments they were anchored in.

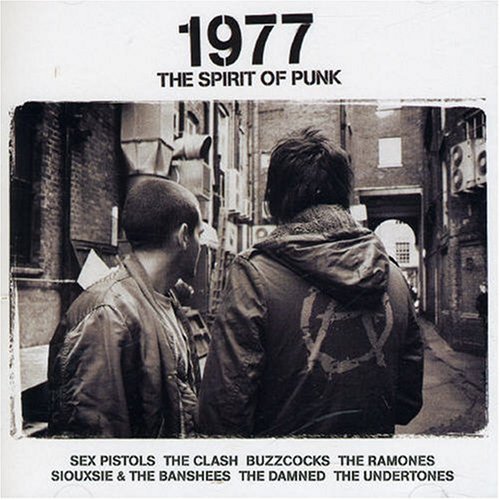

He goes on to paint a picture of the mentality of Britain in 1977, which he says was “the year of the silver jubilee and punk, Britain fractured and filled with self-hate.” Moore couldn’t take the role seriously because nobody, at this point, would have taken Bond seriously. Even though filmmakers at the time were drawn to gritty crime dramas, the only other contemporary British movies with any continued clout at the box office were sex comedies. Consider the following box office successes:

Percy (1971) and its sequel Percy’s Progress (1974). About a shy guy whose penis is mutilated when a naked man falls from a high-rise and lands on him.

Confessions from a Holiday Camp concludes Robert Askwith’s Confessions, a series of sex farces that had aspirations no greater than following the erotic adventures of a guy named Timmy Lea. The plot of each could be described as “male protagonist finds himself in compromising situations with women.” Four of these movies were made between 1974 and 1977.

The long-running Carry On series reached the mainstream with Carry On England (1976). The plot concerns a mixed-sex anti-aircraft battery in wartime who preferred to “make love not war.” A plot that also highlighted the “nagging patriotism” that predated the Thatcher years.

If we consider that Bond at this moment in time has been a slave to popular cinematic trends, it almost goes without saying that some of this particular brand of popular culture would seep into the proceedings. Bond, however, didn’t need the overt titillation driving the success of the sex comedies (Bond had always titillated) but he wouldn’t mind borrowing some of the farce, thank you very much.

Not that I’m saying it’s any good, you’re saying that Connery couldn’t have made, say, The Spy Who Loved Me even if he wanted to?

A serious Bond in 1977 would have been the somber fellow who lingers too long at a party, talking about a recent breakup in between the sorry state of contemporary politics and global warming and ultimately overstays his welcome… but once he’s overstayed, he doesn’t know how to make a graceful exit so he just passes out on the couch. At first he’s just pathetic, so you don’t kick him out, but then he’s still there at breakfast. After a few outings with that guy, you start inviting Roger “Party” Moore to the party. Party Moore arrives, fashionably late, in Sansabelt slacks and a cravat. He never laughs at the jokes of your other guests (who aren’t half as brilliant as they think they are). Instead, he smirks and raises an eyebrow. He then engages them on with thoughtful questions and a wry sense of humor, perhaps telling one or more likely tasteless, probably sexist jokes of his own before leaving, not too early, with the prettiest girl at the party… who also happens to be twenty years his junior.

Bond needed Roger Moore in the 1970’s. In light of all that was happening in Britain at the time, Moore seems more like a pragmatic solution than the blight on the Bond series that many profess. The Guardian (yes, it seems The Guardian has much relevance here) calls The Spy Who Loved Me “a resplendent feather in the cap of Roger Moore apologists.” And while I love the phrase, I loathe the suggestion that to like Roger Moore means I must first pre-empt my affection with an apology. This directly recalls my last discussion about “Guilty Pleasures and The Man with the Golden Gun.” Why should I feel some kind of shame for enjoying the singular elements that Moore brought to the Bond series? Why should I apologize for appreciating Moore’s snark and cynicism just because others refuse to consider how the unique qualities that Moore brought to the character? These characteristics fell in line with the fragile ideological principles and skepticism of the 1970’s, both stateside and in the UK.

Yes, a handwritten apology to Sean Connery would be apropos…

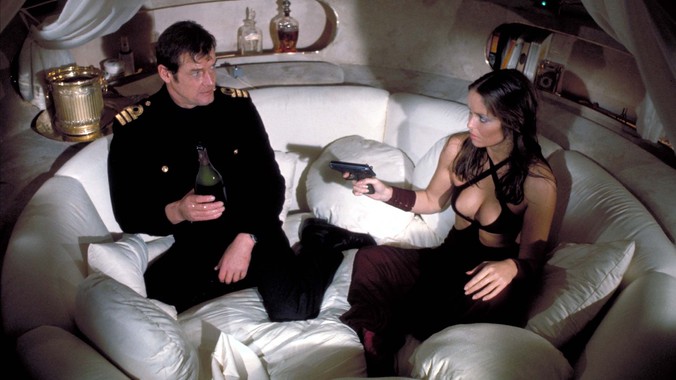

Instead I’m going to cite The Spy Who Loved Me as Moore’s “resplendent feather” in my final appeal for Roger Moore acceptance. The film opens in a lodge on snowy mountain, Moore in bed with a lovely little bird, rolling in fur bedding. His Timex prints out a ticker tape call to duty. “I’m sorry darling. Something came up,” he says. The girl double crosses him, calls in a skiing Russian rifle squad upon his departure. Bond evades, also on skiis. He turns, uses his ski pole as a rifle of his own. And then the signature stunt of the film, a leap from the mountain edge, before deploying the iconic Union Jack parachute. Cue Carly Simon and the lounge-lizard melodies of “Nobody Does It Better.”

Sure, The Spy Who Loved Me falls into the decadent trappings of most Bond films. An overlong, hyper-convoluted plot, intermittently wooden acting, rampant sexism, etc. But for Bond fans, this is part and parcel, part of the hackneyed, predictable charm. It is arguably because rather than in spite of all this formula that we’re granted the brilliant henching of Richard Kiel’s Jaws, an inspired and legitimately feared villain, a villain so dastardly that he kills people by biting them! How fantastically malicious considering these milquetoast modern Bond baddies? There’s also the grand production design of Ken Adams on display in Stromberg’s submersible lair. The debut of the aquatic–loving Lotus Espirit. Consider Barbara Bach, perhaps the most capable and confident Bond girl to this point in the series. Furthermore, consider Barbara Bach’s dress that causes both men and women to swoon.

Director Lewis Gilbert has a full arsenal of ideal Bond ingredients at his disposal and he crafts, arguably, the Bond movie most comfortable in its own hyper-absurdity. The re-embracing of the Bond formula as established in Goldfinger, but without the self-loathing present in You Only Live Twice, becomes the innovation essential to resurrecting 007 from the pop-culture morass in which the series was mired through the early 1970’s. The main difference, thus, between Sean Connery and Roger Moore is that Moore acknowledged the absurdity going on around him with a wink and hinged eyebrow, nothing too intrusive, but just enough for the audiences of the 1970’s to recognize that even 007 has come to question the institution of Bond.

Connery’s Bond never questioned, never wavered. The flaws of serious Connery in a Bond universe teetering on the precipice of “the impossible” (as Moore’s films increasingly became), rather than merely “the improbable,” are on display in You Only Live Twice. While the flawed entry offers much for Bond fans to like, Connery just seems disconnected to the world around him and the movie presents itself as a mockery of the series’ own success.

I don’t expect to convince anyone that Roger Moore was the ultimate Bond. That’s not the goal. The goal is to legitimize Moore’s contribution to the Bond series. Connery was the dose of sincerity necessary to establish the franchise and the character. When the franchise became unstable, like Britain in the same decade of great philosophical turmoil, it too needed to be questioned (as mentioned, many critics were already calling for its demise). Moore was the perfect personality to pull off the near impossible task of both celebrating and acknowledging the growing absurdity of the James Bond institution in an increasingly cynical world. After The Spy Who Loved Me the Moore Bonds spiraled out of control and into the realm of camp and comedy – all still enjoyable, still entertaining, but never quite reaching the heights of that one “resplendent feather” that defibrillated the franchise when most everyone was prepared to call time of death.

I’ll leave you with this timeless bit of advice from Steve Coogan (as Alan Partridge), who manages to somehow eviscerate and revere James Bond (not unlike Roger Moore’s overall interpretation of the character) in his skewered reinactment of the pre-title scene from The Spy Who Loved Me.

“STOP GETTING BOND WRONG!”