Horror films are something of a tricky business. As films which bank largely on unique reactions of their audience, it’s sometimes hard to discern the difference between a bad horror film, and one that simply didn’t affect you. For instance, last year’s Sinister is a film that didn’t frighten me all too much, but it shook other people I know to the core, meaning that is must have been, on some level, effective. Sinister was also fairly well plotted and very well acted (for a horror film at least), so while I walked away from it unshaken, I still enjoyed what I had seen. Which is all to say that my personal pick for this week of horror is a film that may not scare every viewer, but should really mess up a considerable minority.

Horror films are something of a tricky business. As films which bank largely on unique reactions of their audience, it’s sometimes hard to discern the difference between a bad horror film, and one that simply didn’t affect you. For instance, last year’s Sinister is a film that didn’t frighten me all too much, but it shook other people I know to the core, meaning that is must have been, on some level, effective. Sinister was also fairly well plotted and very well acted (for a horror film at least), so while I walked away from it unshaken, I still enjoyed what I had seen. Which is all to say that my personal pick for this week of horror is a film that may not scare every viewer, but should really mess up a considerable minority.

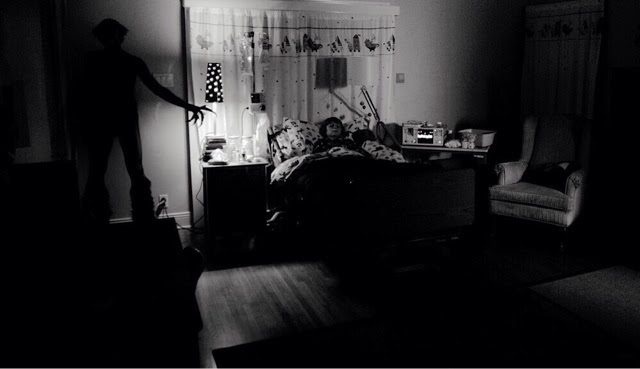

One longstanding principle of horror is the idea that it’s more effective to live the most terrifying things to the imagination. Paranormal Activity uses this principle phenomenally. Not once in that entire series have you ever seen the seemingly omnipresent demon. But it’s presence is felt. And the few hints we get as to what it’s appearance is, animalistic feet, the facial appearance of an old man, are thoroughly unsettling. This founding concept behind this principle is the idea that whatever the human mind can imagine will be more terrifying than whatever creepy creation an art department can design for the screen.

James Wan is the most gifted horror director I know of. In a genre that is filled to the brim with crummy, tactless jump scares and overly crass depictions of graphic violence, Wan has really given time and thought into how to most effectively maximize that art of the scare, what to show the audience and what not to. Wan eschews the traditional concepts of “scary imagery”, such as graphically disfigured ghosts, bloody children, ect. in favor of more subtlety disturbing character designs. Instead of blood and gore, his creepy characters have a deeper nuance to their appearance, suggesting a more pervasive level of evil than graphic, bloody scarring ever could. Wan has figured out that the most disturbing images are the ones where you can’t put your finger on why it’s disturbing. It simply is. It’s easy to point at a woman with her eyes sewn shut and her jaw hanging off and say precisely what’s wrong with her, but it’s much harder to figure out exactly what’s so off about a shadowy old woman in a black wedding dress, holding a candle, who never moves and is always staring from deeply sunken eye sockets. Could it be the juxtaposition of extreme age vs. the youth associated with marriage? Could it be that you can’t tell exactly where she’s looking but you know she’s looking at you? Could it be that the woman in question is actually played by an old man in drag? Is it all of the above? The inability to immediately pinpoint why it’s unsettling only deepens the fear, creating an impression that will last much, much longer than anything you’d see in a typical horror film.

On top of that, Wan has also mastered the timing of how to present these images, he knows precisely how long to display so that the audience can see, but not so long that they can really process what they’ve seen. The result is an effective impression of the image rather than the image itself. A trick of the mind, if you will, one that imprints a visual concept and allows the brain to believe it’s seen something possibly more terrifying than it actually had. It’s a balancing act, one harder to manage than I think most people appreciate, but Wan nails it down like a pro.

Now, all of the praises I’ve given Mr. Wan thus far could also be applied to his recent, and more popular horror film, The Conjuring. So why elevate Insidious over that film when the other clearly made bigger waves? Well, I consider the Insidious films superior because they aren’t just “horror” films, they evolve into something more. While The Conjuring was a deeply effective, traditional homage to classic haunted house movies, the Insidious dualogy is where he and screenwriter Leigh Whannell get to flex their creative muscles. Within these films they have created a unique universe that not only lends itself to horror, but also to science fiction and wide variety of thriller sub-genres. Over the course of the narrative of both films, the story organically evolved without the bothersome restraints of genre to keep it tethered to one train of thought. What starts off as a haunted house flick evolves into a supernatural sci-fi, and in the second film it evolves further into a domestic thriller. It’s an experience that keeps the viewer on their toes, subverting the expectations of genre by simply not applying to any one genre. Right when you begin to track with where you think things are going, the entire game changes, and the story dives wholeheartedly into an entirely new arena.

Insidious and Insidious: Chapter 2 are an absolutely one-of-a-kind two film experience. The first film is a beautifully ambiguous and quirky horror film, while the second not only takes things to the next level, but also fills out and enhances the first film, serving as companion piece rather than an add-on (which is something I feel more sequels should aspire to be). Chapter 2 is cinematic proof that preplanning an entire multi-film saga is not the only way to produce a consistent and cohesive story. Sometimes mining deeper into what’s already been established will result in a fulfilling sequel. These films are scary, funny, weird and fascinating, and there is no other horror film series I would advocate more.

Andrew Allen is a television (and occasionally film) writer for Action A Go Go. He is an aspiring screenwriter and director who is currently studying at the University of Miami. You can check him out on Tumblr @andrewballen and follow him on Twitter @A_B_Allen.