Before we kick off, let me offer some background; for the next couple of weeks I’ve decided to use my Viewfinder column to highlight different series of films that I feel are commendable examples of how to construct a multi-film narrative. First up is The Dark Knight Trilogy.

The Dark Knight Trilogy is easily one of the most unique film trilogies out there, especially in the realm of big budget blockbuster franchises. Three films which together form one, complete arc, following the character of Bruce Wayne from his creation of the Batman icon to his retiring of it. And yet, what makes the trilogy unique is how each film within it stands entirely on its own as a self contained story. Very few trilogies have films which so thematically compliment each other while still standing on their own two feet.

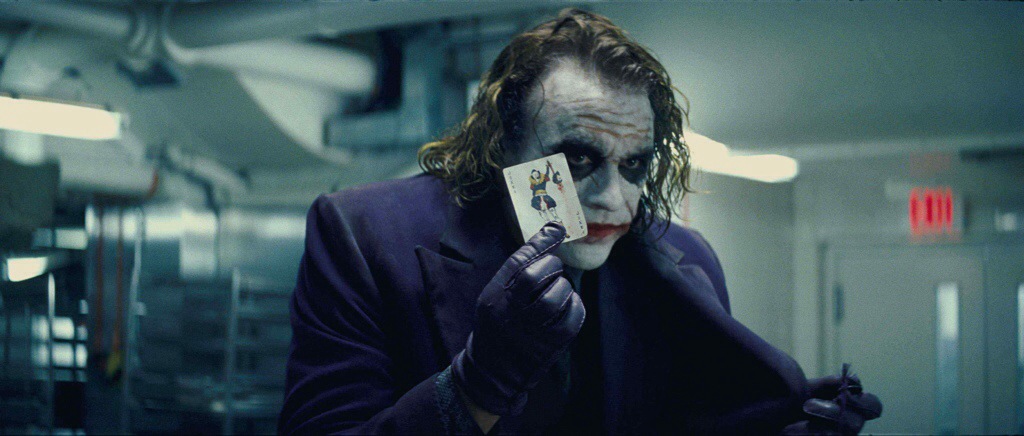

Christopher Nolan has drawn attention, many times, to how the villain of each film represents something completely different from the last. The Scarecrow represents fear, which is the permeating theme of Batman Begins, Bruce overcoming fear in his struggle to become Batman. In The Dark Knight, The Joker represents chaos, the fundamental ideological conflict that a hero who stands for justice and order must face. And finally, in The Dark Knight Rises Bane represents the reality of pain, the suffering that inevitably finds those who stand in the way of evil for the sake of what’s right. Each of which are compelling concepts which build on each other in different ways as the series progresses. But I believe there’s an even more foundational trichotomy at the center of the trilogy.

The Dark Knight Trilogy is not a trilogy of “Batman movies”. Let me get that out of the way first. Iron Man and it’s sequels are “Iron Man movies”, The Dark Knight Trilogy is not the same thing. It is a trilogy of films whose central character is Bruce Wayne, who is Batman, but these films are not “Batman movies”. They aren’t even “Bruce Wayne movies”, although that is a suggestion you’ll commonly hear from those trying to suggest that the focus on the character underneath the cowl is what elevates these films above the rest as some kind of “high art”. The Dark Knight Trilogy is a trilogy of films about superheroes, or heroes in general. It’s far less concerned with showing off its protagonist (nothing wrong with that, that’s all good and fun), than it is with simply asking questions and exploring what being a superhero actually means. The implications of the idea are massive, but consistently play second fiddle to the fact that superheroes are awesome so who has time to sit around and analyze them like a bunch of pretentious scholarly types? And doesn’t that ruin the fun of it?

Well, Chris Nolan has the time, apparently. And although “pretentiousness” is a common accusation thrown at him and his films, I think the man’s interest in Batman and superheroes has alway been a genuine one, even if he doesn’t express that in “traditional” ways.

The trichotomy I referenced before falls in line with the idea that this series isn’t about “Batman” so much as it is about superheroes in the broad spectrum. Each film represents and focuses on a different facet of the reality of superheroes. Batman Begins is about the superhero itself, exploring the rhetoric and experiences that would bring a normal person to use their giftings (whether natural or supernatural) to dedicate their life to defending the innocent from evil doers. Begins seeks to subvert the clichéd concept of what an evildoer really is (bank robber, thief, hoodlum), and humanize it. Bruce Wayne’s attempts to seek vengeance on Joe Chill bring him to a deeper understanding of how people like Chill are driven to violent extremes that result in tragedy. In Batman Begins, the true evildoer isn’t the desperate thief, but the institutionalized selfishness and corruption that creates desperation itself, as well as those who would rather condemn instead of understand. Begins tells the ultimate superhero origin story, while grounding it’s motivation in real world concepts. Batman may be a superhero, but his reasoning for being one is based in truths that the viewer has seen or experienced in everyday life. It’s easy to see human beings in the good/bad dichotomy, it’s much more of a challenge to find the real heart of evil and combat it in a manner that strays true to one’s convictions.

Possibly the most prominent complaint about The Dark Knight is that Batman, the presumed “main character”, gets pushed to the side in favor the the villain; The Joker. I say, well that’s the point! The Dark Knight is about the flip side of the coin introduced in Begins, Dark Knight is a film about the villain. The Joker is the centerpiece here, it’s his movie, because The Dark Knight is just as much about villains in the broad spectrum as Batman Begins was about heroes. I don’t think it’s any kind of mistake that the word “Batman” doesn’t appear in the title for this film, because the filmmakers behind it knew full well that that would not accurately represent what the focus of the film was. The Joker is a manifestation of chaos, and stands in polar opposition of the convictions of our hero, Batman, or even heroes in general. He serves not simply as a follow up antagonist for Batman to fight, but as a representative of villainy as a whole, and his battle against Batman isn’t a violent one, per se, but an ideological one. Joker plays his games on the playing field of belief and conviction, the same one where Bruce forged his ideologies that resulted in Batman. This conflict is the one that cements what the entire trilogy is about at its core: each and every conflict is over somebody’s soul. Each and every conflict is founded in ideologies. When Batman and Joker come to physical blows at the end of this film, it isn’t just a fistfight, it’s a manifestation of the philosophical war that has been growing throughout the film reaching it’s peak. The Dark Knight is a film about the ultimate form of evil that a hero can face, which is the destruction of his convictions, his faith, his beliefs. And in that sense, it does not betray Batman Begins by shoving its “lead” into a corner, but complements it, fulfills it. Not in narrative, but in themes. The Dark Knight is as much a spiritual sequel to Batman Begins as it is a narrative one, drawing from concepts and ideas central to its predecessor, while, from a plot perspective, functioning almost entirely on its own. It’s an interesting and unique approach to sequel-crafting, and one which should probably be adopted by more filmmakers who want to follow up their previous works.

The Dark Knight Rises is the entry that I find the most interesting. Sure, we’ve had the hero movie and the villain movie, what is there left to represent? The central figure of Rises is an essential part of any superhero story, although one regularly pushed to the wayside and taken for granted: The People. Or, The City of Gotham. The essential third element in all superhero stories is the people that the hero has sworn to protect. The role of The People has been reduced to a peripheral one in almost all superhero films, one content with acting as a sort of easily influenced rabble who serve no purpose beyond reacting, in one way or another, to the antics of the heroes and villains. The populace that the hero defends is rarely given a real identity of its own, and that is why I find The Dark Knight Rises so fascinating. The conflict of Dark Knight was between the hero and the villain, The Joker’s goal was to corrupt Batman. In Rises, Bane goes beyond The Joker’s ambition, seeking not to corrupt the defender, but that which he defends as a means of psychological torture for Batman. It’s an interesting take, the idea that the otherwise seemingly witless populace has an identity and a soul worth fighting over. Gotham City has always been something of a personhood unto itself throughout the trilogy; first depicted as a weakened and desperate soul, being poisoned and suffocated by greed and fear in Batman Begins. Then as a stronger, but hardened and dirty place in The Dark Knight. By the time Rises rolls around, Gotham is, on it’s surface, at peace and thriving. But unrest lurks beneath it’s surface like a dam getting ready to burst. It’s this undercurrent of rage and hatred that Bane seeks to manipulate and corrupt Gotham’s soul, a goal only slightly touched on by The Joker in Dark Knight, a goal which Bane largely succeeds at in the third entry. As I stated before, each film in this trilogy depicts a spiritual battle as much as it depicts a physical one. Drawing from classical literature and historical sources, Chris Nolan paints a picture of a city at war with itself. One with an active identity on a level never before really attempted in the realm cinematic superheroes. And although I’m aware that Rises is rather controversial, I would definitely argue that the concept at its foundation makes it the most original and interesting of all three films. Much like a parent unable to protect his own child, Bruce suffers the pain of watching the city he loves tear itself apart through fear and hatred. It cuts down to the very core of what motivated Bruce to don the cowl in Begins, bringing the thematic conflict of the series full circle.

The Dark Knight Rises finds it’s victory not only in the return of Batman, but in the redemption of Gotham itself. The people stand for themselves against the evil they face, inspired by the return of The Batman, no longer content to simply be pawns in a game played by heroes and mad men. The imagery of the Gotham police force facing off against Bane and his army is a powerful representation of how far the city has come since Batman Begins, wherein it was characterized by a crippled civilian populace and a corrupt police force, and it’s fitting that it gets it’s turn in the spotlight as the final piece of the puzzle in The Dark Knight Trilogy. This trilogy belongs to Gotham as much as it does Bruce Wayne, and the city’s soul is the ultimate prize at stake in the end. Wayne sets out to protect Gotham and it’s people in Begins, and much like a child, or a person recovering from illness, the city grows stronger over time, eventually blossoming and standing on its own two feet, side-by-side with the one who protected it and nurtured it for all those years. It’s a beautifully poetic interpretation of the relationship between the protector and protected, the hero and the common folk. It’s inspiring that the ultimate victory belongs as much to the people of Gotham as much as it does Batman, the idea that one man’s noble example can spread to the hearts and minds of the people around him and become ultimately instrumental in that heroes fight. It’s in this way that Batman’s final victory is far more powerful than any onscreen superhero before him: he hasn’t just helped the needy, he armed them with the power to fight for themselves. He inspired and he changed things from how they were. It is often discussed throughout the trilogy that one day the city would, perhaps, no longer need Batman, a thought I always presumed to be a melancholy one. The finale of The Dark Knight Rises proves that assumption to be absolutely wrong. The day Gotham no longer needs Batman is the day that they can claim victory for themselves, which is the kind of power a hero can hold through his or her example, and I don’t believe there’s a higher goal that a hero can attain.

The Dark Knight Trilogy is a stellar example of multi-part filmmaking. Each entry serves it’s own internal purposes while still contributing to the thematic arc of the trilogy as a whole. Unlike many other film series, Nolan never makes any attempt to “recapture the magic” of the preceding film/s in each sequel. Focusing instead on making each film different and unique while not betraying the ideas he established at the beginning. The connections between the films aren’t superficial ones, as is so common in sequels (believe it or not, making tenuous plot connections to preceding films does not a great sequel make). Instead, the series is rooted in consistent concepts and themes, meaning that no matter how much each film varies in tone, it still possesses the same heart and soul that it’s predecessor/s did. Nolan’s trilogy proves that it doesn’t take excessive forthought or convoluted plot threads to create a cohesive trilogy of films. All that is needed is a foundation of strong characters and themes, and from that, the stories can grow naturally. The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises are great sequels because of how unconcerned they are with being sequels. They’re individually great films which just happen to work in chronological conjunction with other great films, no tenuous plot connections required. More writers would do themselves good to work off of Nolan’s example.

Andrew Allen is a television and film writer for Action A Go Go. He is an aspiring screenwriter and director who is currently studying at the University of Miami. You can check him out on Tumblr @andrewballen and follow him on Twitter @A_B_Allen.