Virtually every great musical score in film has a memorable main theme (typically composed by John Williams), one that will have the audience humming long after they leave the theater. Nothing beats a good musical piece that will take you right back into the experience of the movie upon listening to it.

But furthermore, I think every truly spectacular film score has more great themes beyond the main one. Really great musical scores have specific themes for different characters and ideas, ones that will not only draw you back to the film upon hearing them, but to the specific characters or concepts that they’re connected to. This week on Viewfinder I will be taking a look at some of my all-time favorite “secondary themes” in film and television, and figuring out what makes them so “great”.

And so I present to you (in no particular order) the Viewfinder “Top Six Secondary Musical Motifs”.

“A Knife in the Dark”, The Lord of the Rings/The Hobbit

“A Knife in the Dark”, The Lord of the Rings/The Hobbit

Howard Shore’s composition for The Lord of the Rings have a powerful way of striking emotion. The main theme, the one representing The Shire, captures a feeling of warmth and comfort in a way that, I feel, is unprecedented in cinematic film scores. Another feeling Shore’s compositions capture? Fear. “A Knife in the Dark”, the theme most commonly associated with the Ring Wraiths, though it is used in other contexts as well, is one of the most tense and dramatic pieces of music you’ll ever hear in a film.

A dark, operatic choral piece, Shore uses “Knife” to underscore any moment that features an intense showdown between good and evil. The choir vocals swell in a barrage of Elvish chants that sound as if they are the soundtrack of Heaven facing down Hell itself. It’s a stirring piece that just sucks the audience into the moment, and is bound to set hearts racing whenever it plays.

Most Effective Use

I’m going to cheat a little bit here and use two separate examples here.

The first is in The Fellowship of the Ring during what may be the film’s most iconic sequence: Frodo and Co. facing off against the Nazgul up on Weathertop. The scene’s use of slow-motion and little sound aside from the music runs the risk of being over-the-top and melodramatic, yet the intensity of the moment justifies the intense level of drama. It’s a powerful moment in a powerful movie, made all the more powerful thanks to “A Knife in the Dark”.

The second is a similar moment that occurs during The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. At the film’s climax, Thorin finally faces off against his nemesis; Azog the Defiler. The camera dramatically lingers on the faces of our protagonist and antagonist, and then for the first (and at this point, only) time in The Hobbit, the familiar choral voices of “A Knife in the Dark” cut into the scene like… well, like a knife. It was the addition of the music that almost caused me to leap out of my theater seat and applaud such a pitch perfect, and appropriately referential moment.

The loss of John Williams was a very painful blow to the Harry Potter films, and the series almost never quite recovered. The score of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire was something of a drag, and Order of the Phoenix and Half Blood Prince, while decent scores, couldn’t hold a candle to Williams’ magic. It wasn’t until Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows part II, the very last entry, that the musical aspect of the series came roaring back to life with composer Alexandre Desplat, who drew from Williams’ themes as well as the standout material from the other previous composers. Desplat added some themes of his own, the most notable of which is, whiteout a doubt, “Lily’s Theme”.

Lily, Harry’s long dead mother, is a consistent presence throughout the series, and given the importance of her role in the finale, Desplat took it upon himself to make her theme the anthem of the entire film. The piece features a lone, ethereal female voice, singing over a dark string piece. The vocals sound as if Harry’s mother is calling out to him from her grave, with powerful and haunting effects. It’s such a wonderful piece of music that I find it to be an absolute shame that it didn’t find it’s way into the series earlier, if not in the very first entry. But, at the very least, it exists now and Harry Potter is all the better off for it.

Most Effective Use

After a brief prelude recapping the sequence that closed Part I, “Lily’s Theme” opens the final film, playing over the over the opening scene as well as the titles. The scene in question features Snape looking out over the courtyard of Hogwarts as students are marched across the grounds. It’s a grim but poignant series of images that effectively sets the tone for the film to come. Grief and hopelessness possess those opening frames, the music cementing the emotions being conveyed, establishing with absolute finality: this story has gotten serious, and there’s no going back.

“The Lord of Light”, Game of Thrones

“The Lord of Light”, Game of Thrones

Television provides composers with a unique opportunity to grow and develop themes. On Game of Thrones, composer Ramin Djawadi is given a host of characters and families and religions to develop musical motifs for. One of Thrones strongest elements is it’s use of the supernatural. Yes, there are dragons and yes, this is a fantasy show, but there’s something particular about the way Thrones deals with the idea of larger forces at work, unseen, but omnipresent. This can be seen with the White Walkers, by far the show’s most compelling threat, but it can also be seen with the cult of The Lord of Light, led by Stannis Baratheon under the manipulations of The Red Lady; Melisandre. It is this group that is in contact with the sun seen supernatural forces more than any other, and the theme Djawadi composed for this cult is equal parts mysterious yet overwhelmingly creepy.

“The Lord of Light” motif is a simple eight notes, played on repeat, slowly and ominously, on any occasion where the eponymous “Lord” is being discussed or worshipped. The theme serves almost as a stand-in for the powerful deity, who remains, at this point, unseen (which brings into question who, or what, it actually is). The music signifying it’s presence with hair-raising subtlety.

Most Effective Use

The scene where this theme stuck with me most, ironically enough, does not feature Melisandre, Stannis or any direct mention of The Lord of Light. The scene features Lord Varys AKA “The Spider” speaking with Tyrion Lannister, relaying to him the story of how he became a eunuch. It’s a disturbing tale, where Varys reveals that when he was young he had been sold as a slave to a sorcerer. The sorcerer used Varys is a horrific ritual, mutilating him and tossing his man-parts into a fire while chanting in another language. But the part that stuck with Varys the most was not the sorcerer, or the cutting, it was the fact that a voice spoke back from the fire, responding to the sorcerer’s chanting. Though it’s never openly stated, it’s presumed that the voice in question was, in fact, The Lord of Light.

The reason the scene is so powerful is because of how understated it is. Sure, we’ve seen Melisandre use the Lord’s powers to give birth to a demonic smoke-monster, but somehow Varys’ story is far more chilling than actually witnessing such an overtly supernatural display. “The Lord of Light” theme underscores the latter end of Varys’ tale, the slow moan of the instruments adding layers of unsettling mystery to the sequence.

“Davy Jones”, Pirates of the Caribbean

“Davy Jones”, Pirates of the Caribbean

“Davy Jones”, the theme written for the villain of the same name, is pretty much the standard for how to write a motif that encapsulates a character. Davy is portrayed in the film as a tragic character, having torn out his own heart after being deserted by the one he loved; the sea goddess, Calypso. His inner pain seems to be the deciding factor behind every decision he makes, viciously exacting vengeance on those he believes are stupid enough to love another person, a subconscious expression of overbearing self-hatred and profound bitterness. His theme follows the same written music throughout its entirety, but changing speeds and instrumentation reflect different facets of his character.

The music splits into two distinct parts. It starts off slow and sorrowful, playing from a music box (in the film it plays out of a musical locket). There’s a melancholic sweetness to the music, a genuine purity representing Jones’ human side, his lost capacity for love and affection. The second part plays the same theme but this time as an aggressive organ piece (again, one that Jones plays during the actual film). It’s a passionate and aggressive piece, symbolic of Davy’s violent inward state and his transformation from a human being into a garish monster.

Most Effective Use

At World’s End features an emotional scene where Davy Jones and Calypso reunite centuries after their respective betrayals. The theme is used as diegetic sound in this scene, with Calypso listening to it on her musical locket. After shutting the locket, cutting off the music, it begins to play again in a different key from Jones’ counterpart locket. It’s a clever use of representational music in a very literal context.

I consistently forget the fact that “Life and Death” is not, in fact, the main theme of Lost. And while the actual main theme is a powerful motif in its own right, it’s “Life and Death” that had a monumentally profound impact on me during my two-month binge watch of the entire series.

“Life and Death” is the overarching theme that all main themes aspire to be. It perfectly encapsulates the feelings and themes that are fundamental to Lost; the pain of losing loved ones, the fight to hold on to hope, the struggle to survive, all captured with a powerfully melancholic beauty. Whenever I hear “Life and Death” it swiftly takes me back through all the emotions I felt watching Lost. It is the soul of the show conveyed through music, a monumental achievement for composer Michael Giacchino.

Most Effective Use

Without a doubt, the “moving on” sequence that closes the entire show. “Life and Death”, as well as the main theme and a couple other motifs are woven in and out of each other through this piece like a musical tapestry. It also helps that the final scene ponders the idea of simultaneous “life and death” in a manner profoundly more overt than ever before in the series. It’s a beautiful scene and a beautiful orchestral piece that I can’t really describe further without spoiling. Suffice to say, it’s absolute perfection.

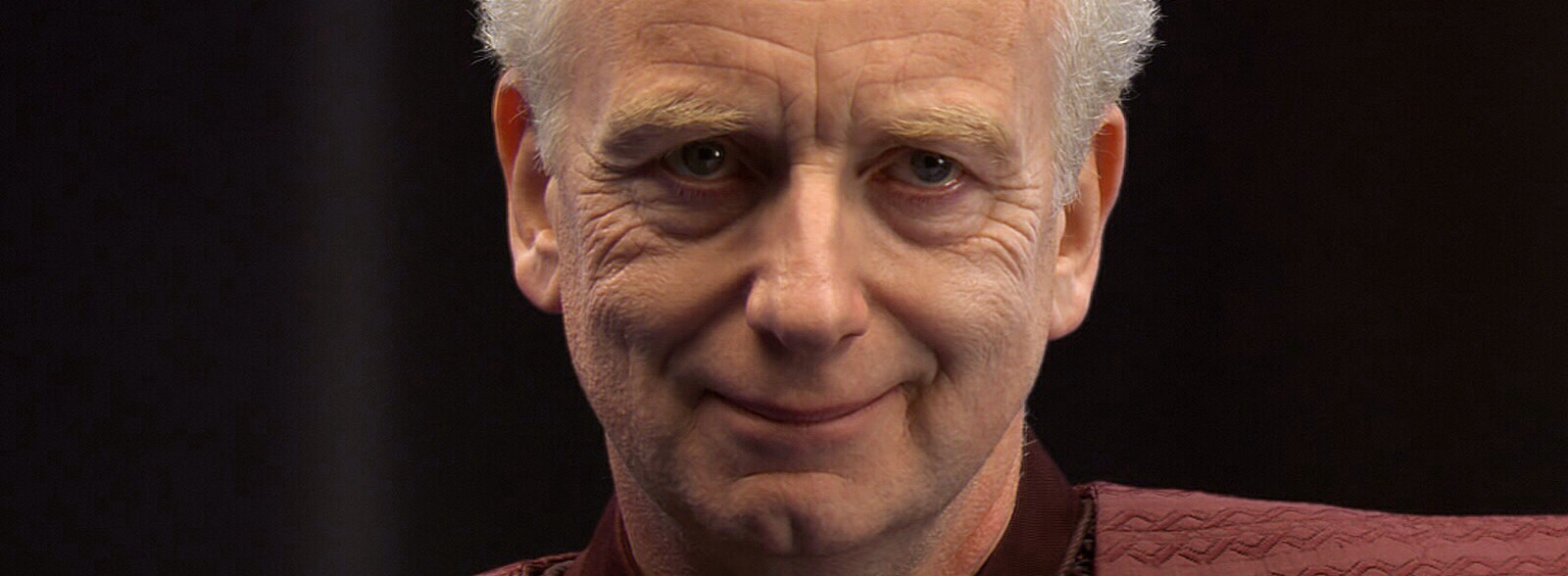

When asking the casual viewer who the main villain of Star Wars is, the answer you are likely to most commonly get is: Darth Vader. Fans of the series, however, know that that is not the case at all. The aptly named Darth Sidious, or Palpatine, is the true antagonist of the series, a title he earns with his insidious deceptions as much as his overt acts of evil. The character’s musical motif is perhaps the darkest musical theme ever featured in a big-budget blockbuster. Unlike most other choral pieces in Star Wars, here the vocals are understated and low; a group of bass vocalists churning out low notes over an almost inaudibly low brass piece. It’s subtle and patient, but also undeniably evil, a musical mirror of the character it accompanies. It’s a piece that, to this day, chills me to the bone when I hear it, and fills me with feelings of dread. John Williams perfectly captures evil hiding in the shadows, a malevolent force watching and waiting from the darkness. Darth Sidious is evil incarnate, irredeemable and unspeakably cruel.

Most Effective Use

The climactic showdown aboard the second Death Star in Return of the Jedi features this theme consistently throughout, each instance growing louder and more powerful as the scene, and Sidious’ plan, progresses. It serves as a reminder of who is truly controlling the events at hand, that Sidious, the unseen manipulator, is the one truly pulling the strings behind both the immediate and overarching conflicts, both of which are simultaneously coming to their close. It’s a fittingly nuanced sequence that effectively neuters Darth Vader as a threat, his villainy being instantly eclipsed by the sadistic, monstrous evil that is Darth Sidious. Vader’s militaristic “Imperial March” doesn’t hold a candle to Sidious’ theme in the dread-conjuring department. Vader may be scary, but he is no more than Sidious’ obedient pet. At least, so Sidious, and the audience, has been led to think…

>

Andrew Allen is a television and film writer for Action A Go Go. He is an aspiring screenwriter and director who is currently studying at the University of Miami. You can check him out on Tumblr @andrewballen and follow him on Twitter @A_B_Allen.<