By Heligena (Guest Contributor)

Have you seen it yet? Gone Girl? David Fincher’s mystery thriller based on the book of the same name? A lot of people clearly have since the film is currently riding high on a “metascore” of 79 and an average review rating on IMDb of 8.7 However, a better question that seems to be on the minds of many of those who have seen it seems to be whether or not the film is misogynistic at heart? I’m going to take a quick look at this argument (I’m sure I don’t have to tell you that there are spoilers within so you might not want to read any further if you haven’t caught the movie on the big screen yet).

So…what does “misogynistic” really mean? The term is traditionally classified as something characterized by a hatred of women. Taking this into account, is the film at its core women-hating? It’s a strange claim considering both the novel and the screenplay were in fact written by a woman, Gillian Flynn. Flynn, an American author and former television critic also gained a Master’s degree from the well-respected Northwestern University. From my perspective, it seems fairly unlikely that any subconscious female-bashing would have escaped such a literary/critical mind. And if purposeful, I can’t really see what she might have gained from the exercise.

Interestingly enough, in the past, Flynn has suffered accusations of misogyny regarding her previously published novels. Perhaps then, there is a grain of truth in the idea. The problem with that kind of thinking is that Flynn actually replied to her accusers, responding quite openly by stating that she felt the depictions of women as innately good and nurturing are incredibly limiting when it comes to the creative process. She has argued that it’s more interesting to write characters that go against the stereotype, characters that make people uncomfortable. It appears then that far from labeling all women manipulative, she is actually using her writing to explore the idea of women as calculating, emotionless beings- in order to make us face up to an idea that causes us great unease. It’s the exact opposite of misogyny as it happens. Jeez, it’s almost feminist.

But back to the movie in question.

What then of the director David Fincher? Could he be a misogynist? His last fictional movie, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, centered around an intelligent, autonomous woman that saved herself from her own sordid past. Zodiac, Fight Club and Se7en may have been bleak, jaded master classes in style but the male characters were just as messed up as their female counterparts if not more so. Is Se7en “misandristic” because the killer is a man? No. It doesn’t imply all men are evil just that particular one. This is also the man who directed Alien 3, one entry in the quintessential female empowerment franchise. As a fan of his work, I’ve got to be honest, I kind of doubt Fincher has a problem with women. More than that, I seriously doubt he’d let it leach into his work if he did.

So past history of the writer and author points to a big fat NO. And in terms of the film, I’ve got to be honest, I’m drawing a big old blank as well. Let’s take Amy Dunne (Rosamund Pike’s character) as the first point. Admittedly, she is a vile human being. At once impassive, detached, incapable of empathy and murderously idealistic. This is not a good person; duly noted. And she is played with disconnected aplomb by the lovely Rosamund Pike. However, she’s also not the only female character in the story. Carrie Coon’s Margo Dunne is spunky, loyal and loving to her brother, even when her own life and reputation hangs in the balance. Kim Dicken’s Detective Boney is also smart but taciturn, observant, measured and intellectual despite the prejudices surrounding her. In fact the male cops she works with are collectively much more ignorant and prone to letting their emotions rule their behaviour. So on that score the movie could technically be classed as misanthropic if anything. Especially since it shows people to be flawed regardless of their gender. What it actually seems to be saying is that all women are not evil, but some people are, and Amy Dunne happens to be one of them.

The first third of the film focuses solely on husband Nick Dunne’s perspective of events. Literally, we are drawn into the story through his eyes and his confusion. Amy’s view on things is not even hinted at until the viewer has formed an emotional connection with Nick since he is the only protagonist on offer. To play devil’s advocate, that perspective in itself might lead to some vague anti-women sentiments. But to counteract this, Amy’s story then directly follows, changing everything that we thought we knew. Her version of events effectively rewrites history (and it’s worth noting the use of a diary she falsely creates), and this is not the sort of power a woman-hating movie maker would give out easily. The final third morphs into a shared, tale with both husband and wife existing in the same narrative space together. There’s a balance that emerges, even though you could argue Amy seems to have the upper hand in terms of plot. This merging of male-female perspectives at the conclusion only convinces me further that the film couldn’t be less misogynistic if it tried. It’s equal opportunity judgement. Again, misanthropic if anything.

It’s not a coincidence either that Amy’s temporary downfall at the motel where she’s hiding out comes at the hands of both a girl and a guy. Whereas Amy’s manipulations have given her a great deal of success so far, her plans are completely derailed by male and female con artists working together to rip her off. The fact that they then make off with her money wihout retribution just underlines the film’s attitude that true advancement only seems to stem from gender co-operation. So again, it’s not about women…it’s about people.

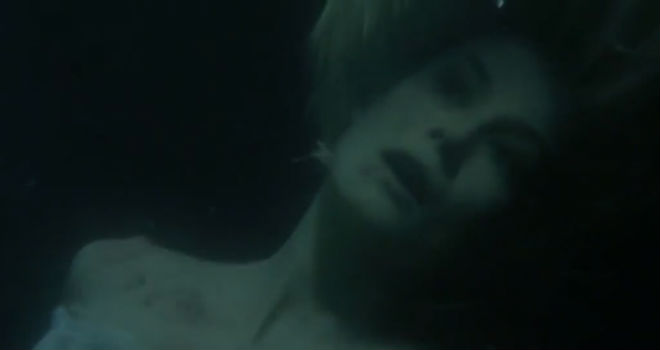

Anyone still with me? Ok. Cool. Well, luckily we’re on our last point and here it is…the reunion scene. You’ll remember the one, it’s the best scene in the movie. Where Amy returns home in front of the world’s cameras and falls into her husband’s arms, blood covered negligee and all. If you ask me, that would have made a hell of an end scene, more Fincher-esque than the actual conclusion, leaving the viewer to wonder what these two characters might do next. But that’s a side note. When Affleck leans in and whispers “You fucking bitch” to his wife, she smiles lovingly for the press barrage on her front lawn. That image of the two of them — isolated from the people watching but front and centre in their own personal drama — screams one single message. That this is one couple locked in their own nightmare; separate from the world judging them, a world unaware of the real story unfolding. They are individuals not representations of humanity. And any malice that exists between them is theirs alone. Not women’s, not men’s…but theirs.

I’m sure those accusing the film of misogyny have their own arguments to back up their opinions. And good luck to them. But for me, that type of thinking is misinterpretation at best and prejudice at worst. I stand by the film despite all its flaws (an over-exuberant running time for one, an understated sense of directorial style for another), and I’d ask those critics why can’t they just enjoy a film for the compelling piece of cinema that it is?

Heligena writes for Off The Record On The QT. She is a glasses-wearing movie nerd with a yen for graphic novels and over-filled bagels. You may have already passed her on the streets of Cardiff…you probably didn’t notice her but I’m betting she noticed you.