For many people “classic” means boring or arty or esoteric. But that door swings both ways. Movies or actors can be slapped with reductionist manifestos, often crafted by people who never took the time to watch the films themselves. Like those that consider the Marx Brothers just another slapstick routine. That Chaplin wasn’t funny (as if his timeless pathos wasn’t at all relevant). Or that Burt Reynolds was just a product of the 70’s, a southern cad that made a bunch of good ol’ boy comedies.

I’m having a hard time recalling my first exposure to Burt Reynolds. There was always Burt Reynolds. I was a little young to remember Burt during the late 70’s when he was the biggest star in Hollywood for five consecutive years – a feat that’ll likely never happen again.

Unless I’m terribly mistaken my first memories come from seeing The Cannonball Run on television. I couldn’t have been more than 6 or 7 and I likened Burt to a live action Muppet. The perfect, exaggerated mustache, the Fozzy bear laugh. And for many years that remained my impression of Burt Reynolds. Live action Muppet Burt and not that other Muppet Bert – sorry Bert, but there’s really only one true Burt. Wise beyond my Sesame Street years.

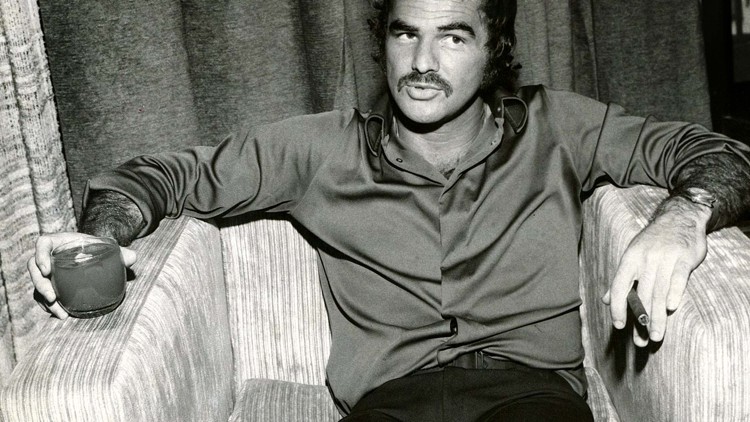

But it wasn’t until the last decade that I expanded my understanding of Burt Reynolds beyond the car driving, American beer drinking ham that came to dominate his public persona. Burt was first and foremost an entertainer – you can see this is in all of his performances – even when he took dramatic roles in films like Boogie Nights and appeared to take great pleasure in ribbing his own legacy in the animated TV series Archer.

As a result of his massive commercial appeal, we also tend to forget that Burt was a damn fine actor and an underappreciated director (Sharky’s Machine remains a minor masterpiece of the 1980’s) that never saw a real opportunity to explore his craft behind the camera.

Burton Leon Reynolds was born in Lansing, Michigan in 1936. I was born an hour north in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan. A straight shot up Michigan Route 127 and 42 years apart. I feel a kind of displaced Michigander kinship.

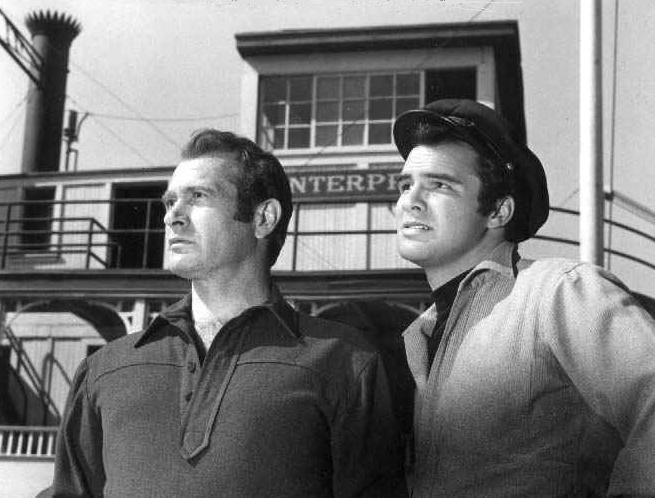

After his father returned from World War II, his father moved the family to Riviera Beach, Florida where Burt eventually earned a scholarship to play football at Florida State University. After a car accident and a knee injury derailed his hopes of playing professional football, he dropped out of school (stay in school, kids) and headed to New York to become an actor. While waiting tables, taking one-off TV spots and working the stage, he was given the opportunity to play a regular character on the show Riverboat opposite Darren McGavin.

After knocking around television for a number of years, Reynolds got his first starring role in a forgettable espionage drama called Operation C.I.A. (1965). He then began a string of three Westerns in which he played a man of Native American descent. Burt Reynolds’ big break came in 1972 when he appeared in John Boorman’s iconic backwoods thriller Deliverance (1972). Anyone who claims that Burt Reynolds couldn’t act needs to revisit his starmaking performance in this film and 1974’s The Longest Yard, where he showcased not only his innate skills on the football field but also a deft balance for comedy and drama.

Burt became “Burt” once the public latched onto that flash of charisma, that laugh, that smile, that easy charm. The public demanded more and more, and Burt found the quality of his roles dwindle. The dark side of being the biggest star on the planet.

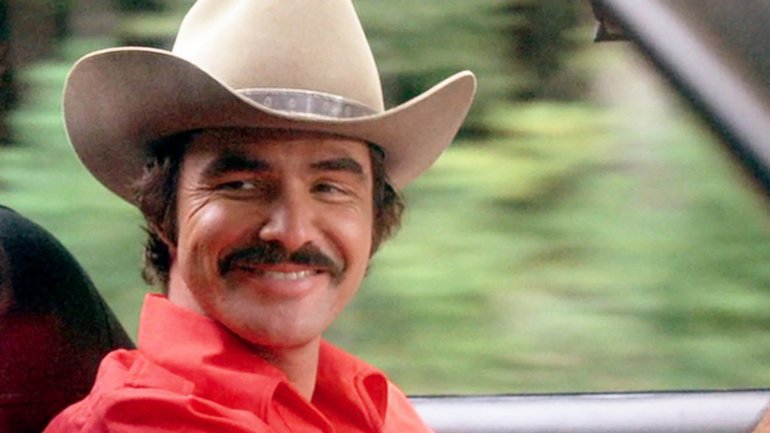

He’d reached the pinnacle of showbusiness. The most famous man in America, but in many ways Reynolds’ career never recovered from his success. Whenever he tried to break away from his good ol’ boy southern charmer on a bearskin rug persona, the public cried foul and the critics failed to take him seriously. He dabbled in musicals, comedies, satire – some of his best and bravest work came in movies that were critically reviled or publicly shunned. That he failed to more fully realize his potential as an actor and a director was an outcome partially of his own making, but also because the business of show witnessed the success of Smokey and the Bandit and demanded more for as long as Burt was willing to give it.

He’d reached the pinnacle of showbusiness. The most famous man in America, but in many ways Reynolds’ career never recovered from his success. Whenever he tried to break away from his good ol’ boy southern charmer on a bearskin rug persona, the public cried foul and the critics failed to take him seriously. He dabbled in musicals, comedies, satire – some of his best and bravest work came in movies that were critically reviled or publicly shunned. That he failed to more fully realize his potential as an actor and a director was an outcome partially of his own making, but also because the business of show witnessed the success of Smokey and the Bandit and demanded more for as long as Burt was willing to give it.

Look not to Smokey and the Bandit for Burt’s most “Burt” moment on screen. That honor likely goes to the Hal Needham-directed stuntman action/comedy Hooper, in which Burt plays “the Greatest Stuntman Alive,” once again alongside Sally Field. The movie championed the unseen work done by the stuntmen and stuntwomen of cinema. In the end, Burt sticks it to the man (the pretentious auteur director/Peter Bogdanovich parody) and has a damn good time doing it. Needham directed the film as a love letter to the stuntman, aka the underrecognized working man, and Burt perfectly embodies the hell-raiser just trying to survive that one last jump.

On an interview with Johnny Carson in 1979, Reynolds admitted that he dreamed of winning an Academy Award, to be rewarded for his craft by his peers. While he would go on to win an Emmy for his work on the CBS hit comedy Evening Shade, he received only one Oscar nomination for his supporting role in Boogie Nights (1998).

There’s an innate tragedy in knowing that the man never realized his dream even though he appeared to have it all. Burt Reynolds died Wednesday at the age of 82, but he’s left us a wide and varied cinematic legacy that many have yet to truly appreciate or discover. He was a singular personality, the Bandit, a mustache, the laugh, some snarl, a womanizer, a cad, an athlete, a legend, a straight-shooter, a kid from Lansing, a real goddamn movie star.

He was just Burt.