The best horror films, I believe, are the most compact ones. The most effective horror films are those that are so tightly wound that they feel claustrophobic, both in environment and narrative. This is why when people reminisce about the scariest films they’ve ever seen, it is common to hear reflections on an old episode of The Twilight Zone that really gave them the heebie-jeebies. Twilight Zone‘s TV-grade budget and short runtime forced it to create extremely simple, yet tightly wound stories that could be set up swiftly and just as swiftly unraveled once the climax hits. Paranormal Activity, like Twilight Zone, has a hyper simplistic premise and it is also completely isolated in a singular location. As the tension grows, the claustrophobia of the situation becomes stifling, there’s nowhere to go on both the environmental level; you’re stuck in the house, and on the story level; there’s no B-plot to conveniently cut away to. Many films have featured variations of this set up, the most successful ones being those that either stick extremely close to it (Evil Dead) or find a legitimately clever way to subvert it (Insidious).

Which brings us to Mike Flanagan’s Oculus, a high-concept horror film that, for all means and purposes, should lend itself perfectly to this format, yet doesn’t. At least, not as much as it should have. Most of Oculus‘s runtime is comprised of exactly that claustrophobic set up; characters trapped in a house, no outside narrative to cut away to. But for the first fifteen or twenty minutes, the story provides too much breathing room. The film’s first act is exposition heavy and largely tension-less, providing no particular reason for the audience to be engaged in it’s proceedings. Characters are introduced, plot points are vaguely alluded to, foreshadowing occurs, all in a manner that feels rote and stale. We see the characters at work, at an auction, in a warehouse. The few scares that are attempted feel largely inconsequential because, as an audience member, I never felt trapped in those moments. Never felt stifled in any way by the tension that was being attempted. None of the execution here is truly incompetent, it’s just that none of it feels purposeful or worthy of attention, and none of it feels contained in the way horror movies of this kind really should.

Things get rolling when our two lead characters, a brother/sister duo played by Brendan Thwaites and Karen Gillan, find themselves in the house where most of the action takes place and the actual point of the story is unveiled. It’s at this spot in the narrative that I have to ask; why on earth would you not start the film here? Oculus would’ve benefitted significantly in the areas of tone and plotting if all of the action had been confined to this scenario from the get go. Allowing the audience to see so much of the outside world, and for seemingly no particularly compelling narrative purpose, sapped the film of it’s energy and drained a lot of the goodwill I was predisposed to having going into the theater. Thankfully, Oculus picks up steam quickly, and once the actual horror element kicks in, things get very intense, very fast.

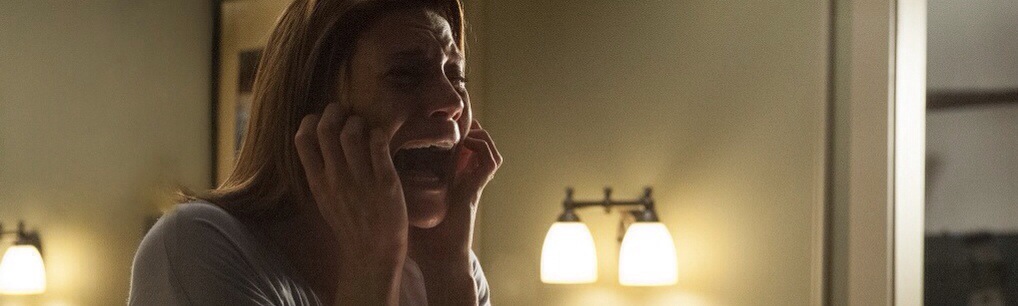

Most of the horror in Oculus is based on the concept of perception. The film’s antagonist, a spirit-possessed mirror, has the ability to manipulate what those within a certain proximity to it can see, hear and feel. It uses this ability to try and manipulate it’s victims into killing themselves or each other. Neither the characters nor the audience can ever be sure what they’re seeing on screen is “real” or an illusion perpetrated by the mirror. The effect is something of a descent into madness, very much Twilight Zone-esque in it’s execution, with the characters having to second guess every action they make, as it could mean the difference between life and death. The film also leaps back and forth between present day action and events that took place eleven years prior, during the protagonists childhood. As the film progresses, the horror they are currently experiencing begins to mimic that which they experienced in their childhood. With some clever camera work and actor-switching, director Mike Flanagan keeps the story rolling between these two plot threads without ever missing a beat. With both narratives following the exact same plot points, he can follow one story while still effectively informing the audience about what’s happening in the other, never resorting to backtracking or over explaining. The set up is brilliant, and, surprisingly, most of the film lives up to the concept’s potential. Admittedly, the “rules” this thing plays by are fairly vague in the first place, so ultimately I can’t entirely be sure any of the film makes actual sense. But, it, at the very least, maintains the illusion of internal logic well enough that I never found myself questioning it during the film itself, keeping the tension intact.

The performances are only serviceable, for the most part, Katee Sackhoff as the mother of Gillan and Thwaites’s characters being a notable exception, delivering an intense and more nuanced performance. Also Annalise Basso and Garrett Ryan, playing young Gillan and Thwaites, are surprisingly competent for actors their age, both possessing an impeccable ability to exude convincing fear. The rest of the cast; Gillan, Thwaites, Rory Cochrane as their father, and James Lafferty as Gillan’s fiancé, all deliver fairly standard horror performances. And by that I mean that they’re okay. Not bad, not great, just serviceable. With the acting bar having been raised over the past few years by films such as The Conjuring and Sinister, it’s hard not to feel like this film could have really upped it’s game with the truly top-notch level acting of those films. Luckily, Oculus banks on its highly effective concept far more than it’s performances, so this is only a minor quibble.

Oculus ultimately make good on it’s conceptual promise despite some fairly pedestrian performances and a drag of a first act, delivering some seriously high-strung, creepy entertainment. It should entertain both horror junkies and the casual viewer alike, and the concept alone is worth the ticket price. It may not be the all-time horror classic it could have been, but it’s still good, and fairly unique, fun.

Andrew Allen is a television and film writer for Action A Go Go. He is an aspiring screenwriter and director who is currently studying at the University of Miami. You can check him out on Tumblr @andrewballen and follow him on Twitter @A_B_Allen.