By Andrew Allen

“Fans are very opinionated, and that’s good. But I can’t make a movie for fans.” – George Lucas, 2002

On April 16, Star Wars fans gathered in Anaheim, California for Celebration Anaheim, which would turn out to be the most eventful Star Wars-related gathering of the past decade. Director J.J. Abrams and executive producer Kathleen Kennedy both attended the convention to unveil promotional material for their upcoming Star Wars: The Force Awakens, the seventh entry in the franchise and possibly the most anticipated film of the past fifteen years (at least). Most importantly, Abrams and Kennedy, presented for the first time an all-new trailer for the film, a trailer which practically sent the convention and the whole internet ablaze with excitement.

Fans rejoiced, grown men wept, and most everybody agreed: the future is looking very, very bright for Star Wars

Or so it would seem

To understand why The Force Awakens trailer was such a huge event, one must first understand the history of the Star Wars franchise. The nutshell version of it is this: back in the 70’s and 80’s a writer/director named George Lucas ushered into existence a trilogy of films that garnered a dedicated following on a scale and with a fervor that the film world had never before seen.

Naturally, it couldn’t just end at three films.

Sixteen years after the third and final entry of the original Star Wars trilogy, Lucas released a new film, a prequel titled Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace with the intention of launching an all-new trilogy of films. The fans were less than pleased. In the years since, public opinion of Menace has declined sharply. What was once regarded as a mere disappointed has somehow transformed into something of a heretical crime. To speak highly of The Phantom Menace is to speak heresy, foolishness, idiocy (despite, it’s worth noting, numerous positive reviews of the film by critics such as Roger Ebert). The two following prequels; Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith fared only moderately better with Sith opening to fairly universal praise, only to decline in the public eye in the ten years since.

Common complaints about these prequels were the perceived overuse of CGI visual effects over practical ones, a slicker, smoother design scheme unlike the gritty, textured style of the original films, and a general lack of expectational fulfillment. To many who grew up on the original movies, Episodes I, II and III aren’t just lackluster movies, they’re not even truly Star Wars.

Common complaints about these prequels were the perceived overuse of CGI visual effects over practical ones, a slicker, smoother design scheme unlike the gritty, textured style of the original films, and a general lack of expectational fulfillment. To many who grew up on the original movies, Episodes I, II and III aren’t just lackluster movies, they’re not even truly Star Wars.

And so, we have The Force Awakens. J.J. Abrams takes over for George Lucas, whose role in the new film is in credit only. Abrams and his production team have made it their goal, their duty, to return Star Wars to it’s former glory. Practical effects, a rugged aesthetic, reverting to shooting on film stock as opposed to digital, the return of popular characters from the original three movies. The new trailer showcases these elements proudly, ending with a shot of the beloved Han Solo and his sidekick Chewbacca. “Chewie, we’re home” says Solo, the two of them meticulously positioned to replicate a famous promotional image from the very original Star Wars.

The fans went wild. A great time was had by all. Abrams’ new trailer gave the fans exactly what they demanded in bucketloads.

But is bowing to the demands of a zealous fanbase the way to make a great movie?

For all it’s crowd-pleasing showmanship, one could very easily say that The Force Awakens trailer offered very little on it’s own merit. It deals almost entirely in sentiment and the use of established, iconic imagery to elicit emotional reactions from it’s audience. For the most part, nothing of what we’ve seen so far in The Force Awakens is particularly new or exciting, rather, it’s mostly just riffs on established material that will prove familiar to the fans, or even anyone who has lived in a first-world country anytime since 1977.

My point? Art is not made by committee.

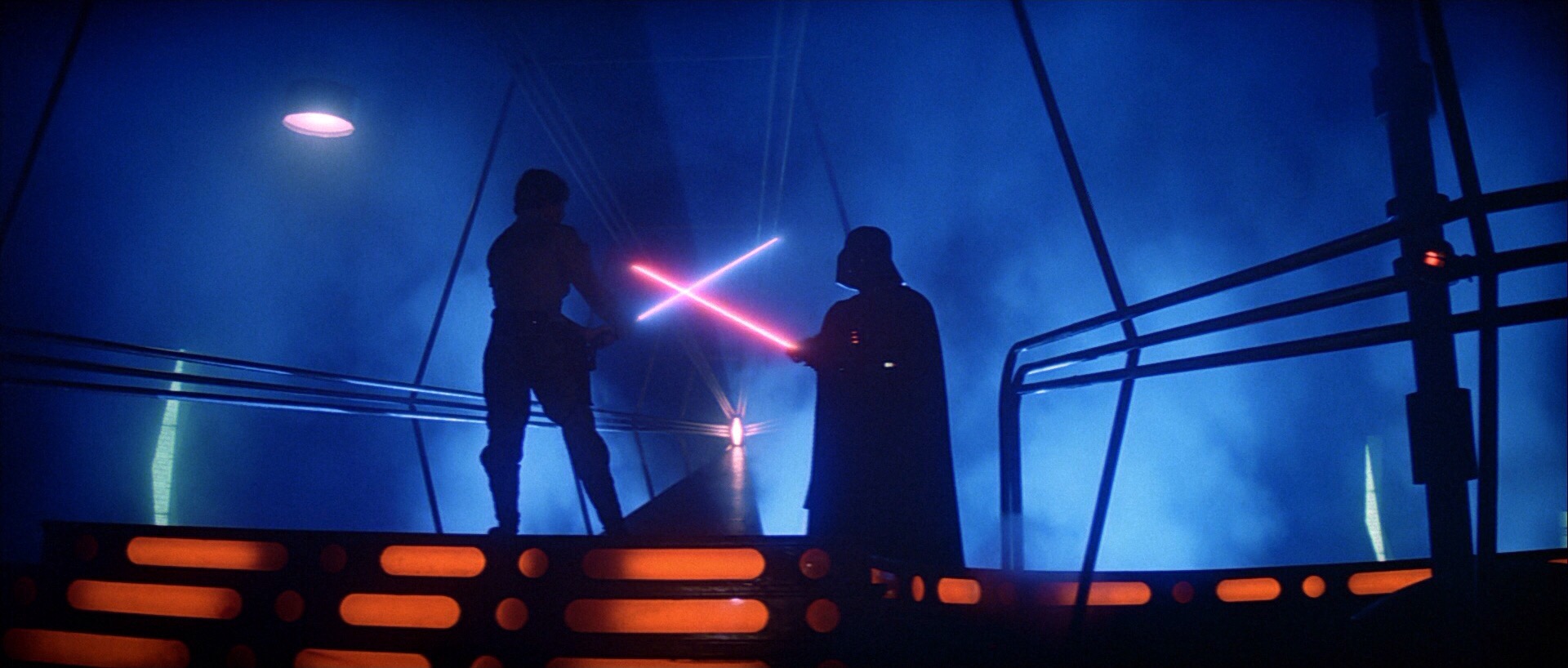

Now, most everybody would agree with that. Nobody wants some heartless board of executives decided what to do with a beloved movie series. But I believe it’s worth positing that there is, perhaps, an even worse sort of committee than entertainment industry executives: a possessive, demanding fanbase. The problem with fans, despite what they contribute to a series monetarily, is that they’re only fans of what they know, what they’re familiar with, what they understand. A fanbase, by definition, can’t demand something new and exciting out of a sequel because they aren’t fans of something different, they’re fans of something that already exists. So, despite the best intentions, fans could never make renowned films like The Dark Knight, Aliens or even The Empire Strikes Back happen. Why? Because those films were unprecedented. They took a previously established property, flipped it on it’s head, and produced something new, daring, compelling, visionary. Because that’s what art is. That’s what an artist with a vision can create. Something a horde of thousands upon thousands of fans with restrictive demands and preconceived notions could never accomplish.

Despite the criticisms launched against them (some of which I agree with, most of which I don’t), the Star Wars prequels were, perhaps, three of the last examples of directorial freedom and artistic license in big-budget blockbuster cinema. George Lucas made the films he wanted to make on a huge scale; no executive, no studio could stop him and what he wanted to do. He was an artist with a vision. Not everybody liked that vision, ultimately, but it was still a vision. It was uncompromised. It was art. Very, very few movies on that scale ever get made that way anymore. Too many parties investing too much money in the final product to hand the reins over to a single artist free of studio micromanagement. Whatever it’s ups and downs may be, the Star Wars franchise in it’s entirety has been a humongous victory for artistic freedom in the big-budget sphere.

Despite the criticisms launched against them (some of which I agree with, most of which I don’t), the Star Wars prequels were, perhaps, three of the last examples of directorial freedom and artistic license in big-budget blockbuster cinema. George Lucas made the films he wanted to make on a huge scale; no executive, no studio could stop him and what he wanted to do. He was an artist with a vision. Not everybody liked that vision, ultimately, but it was still a vision. It was uncompromised. It was art. Very, very few movies on that scale ever get made that way anymore. Too many parties investing too much money in the final product to hand the reins over to a single artist free of studio micromanagement. Whatever it’s ups and downs may be, the Star Wars franchise in it’s entirety has been a humongous victory for artistic freedom in the big-budget sphere.

Until now, anyway.

The problem with artistic freedom is that it runs a much higher chance of an artist taking risks that their audience really does not like. And when one has a fanbase as large as Star Wars, that dislike can turn toxic, and the fanbase can actually cheer for loss of artistic and creative freedom. The very freedom that created the movies they so loved in the first place.

If there was one point that J.J. Abrams and Co. nailed home repeatedly over the course of Celebration, it’s that pleasing the fans is of the utmost importance to them. The Force Awakens is “for the fans”, to satisfy their demands, to ease their fear that Star Wars would continue to be something they find unfamiliar, outside of their comfort zone. Will that mean that The Force Awakens will be a bad film? By no means. But it also has a very, very slim chance of being a great film, like The Empire Strikes Back or (yes, I mean this sincerely) Revenge of the Sith. Why? Because no great film has ever been made by bowing to the whims of an overwhelmingly vocal majority. No truly great film has ever been made when an artist is so thoroughly hemmed in aesthetically, tonally, stylistically as these creatives have been on The Force Awakens. No truly great film has ever been made when attempting to recapture and imitate the spark of a past film’s genius.

The Force Awakens could prove to be quite a bit of fun. But if it shapes up to be the pandering, nostalgia-baiting piece of cinema that it’s marketing itself as, it has no real chance of being a great movie. If this mission statement of fan-appeasement becomes the modus operandi for the Star Wars franchise moving forward, it’s days of true excellence are assuredly well behind it. Fans may say there’s nothing sadder than seeing a franchise grow into something unfamiliar, different in flavor than how it originally began. But it may be sadder still to see a once-great testament to the power of creative freedom reduced to sycophantic, self-regurgitating drivel. Enslaved by it’s own adherents, doomed to chase it’s own tail for eternity, hopelessly attempting to recreate brilliance that, ironically, can only be created through creative risk and artistic freedom.

Practical effects, film stock and Harrison Ford can’t “save” Star Wars. Only a writer and a director with a new vision and the freedom to create, regardless of what that entails, can really do that. Safety and familiarity are the death of art. And if fans, critics, and whomever else can’t bear the risk of potentially hating a Star Wars they aren’t yet familiar with, then their beloved movie series is, to put it simply, doomed.

Practical effects, film stock and Harrison Ford can’t “save” Star Wars. Only a writer and a director with a new vision and the freedom to create, regardless of what that entails, can really do that. Safety and familiarity are the death of art. And if fans, critics, and whomever else can’t bear the risk of potentially hating a Star Wars they aren’t yet familiar with, then their beloved movie series is, to put it simply, doomed.

Art is not made by committee, regardless of whether that committe is penny-pinching studio executives or nostalgia fixated fanboys. Let’s fight to keep it that way.

Andrew on Twitter | Action A Go Go on Twitter and Instagram |Be sure to leave your thoughts in the comments section!

Andrew Allen is a television and film writer for Action A Go Go. He is an aspiring screenwriter and director who is currently studying at the University of Miami. You can check him out on Tumblr @andrewballen and follow him on Twitter @A_B_Allen.

The views and commentaries expressed on these pages are solely those of their authors and are not necessarily either shared or endorsed by ActionAGoGo.com.