That’s right, we’ve all been lied to, folks. And badly.

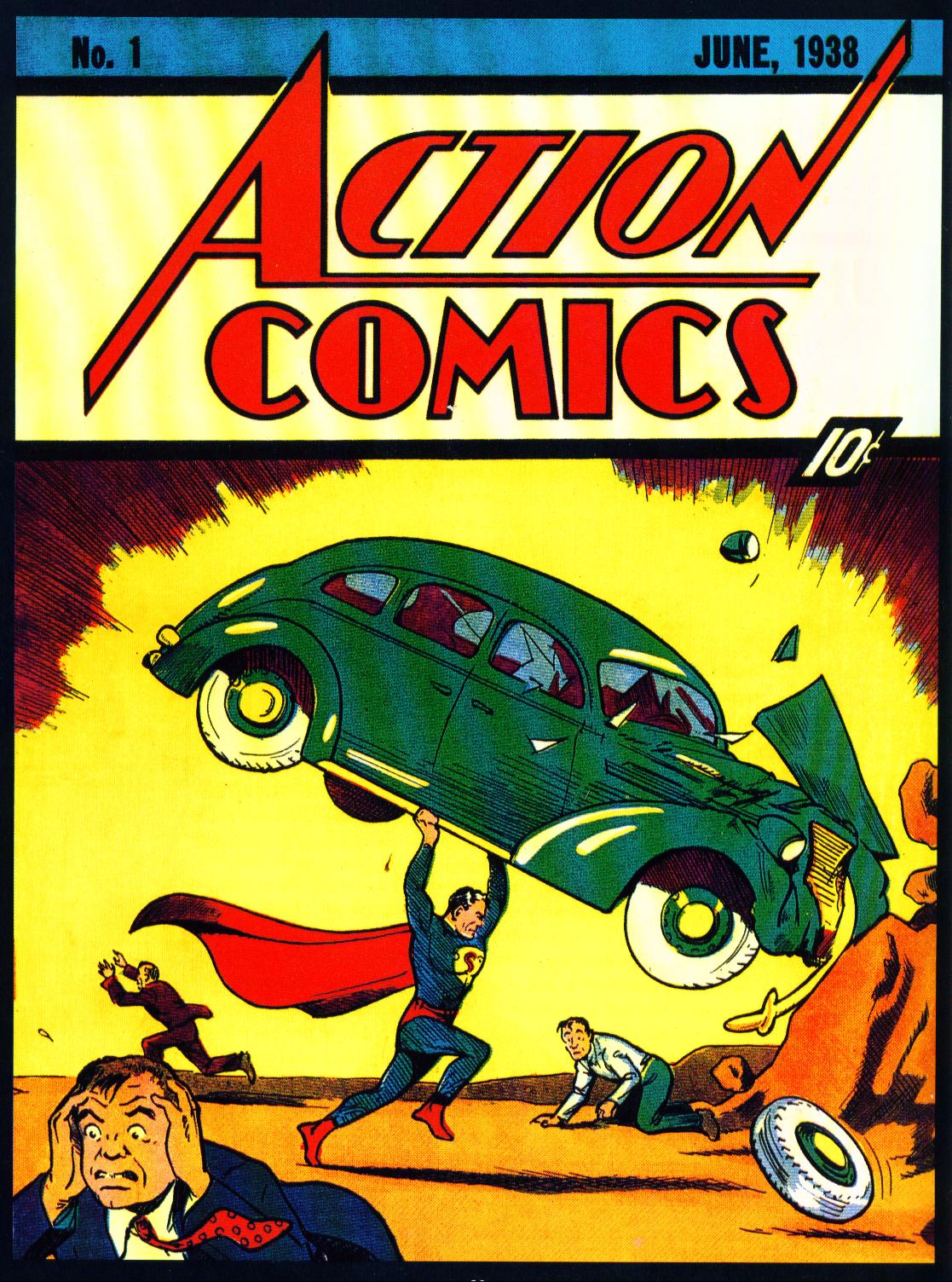

Ask any comic book historian or dyed in the wool geek when the Golden Age of comics kicked off and they will undoubtedly say the late 1930s and 1940s. For comic books, that particular era is marked by the first appearance of Superman in 1938’s ACTION COMICS #1 (now on its 1000th issue) and concludes right before the end of the following decade. This period was characterized by pop culture mainstays like Captain America, Batman, Wonder Woman, and Captain Marvel. Even further, books featuring these icons performed incredibly (1939’s SUPERMAN #1 had over one million copies in circulation), and often highlighted unabashed patriotism as well as non-ironic acts of heroism.

This, of course, laid the foundations for what the superhero would become in later generations. The Golden Age was followed by the Silver Age (the 1950s to the late ’60s) and the Bronze Age (1970 to 1986). During these periods, comics and their heroes gradually grew more complex and tackled more adult themes. Needless to say, the clearest indicator of the format shifting to mature content came in the form of WATCHMEN, written by Alan Moore and drawn by Dave Gibbons. This legendary 12-issue run turned the notion of being a superhero on its head, tackled heavy adult themes such as mental illness and sexual assault, and added layer upon layer of complexity that could rival the most acclaimed literature of the day.

If the mind-bending Watchmen wasn’t enough, Frank Miller dropped a bomb on the industry with THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS. This seminal work reinvented the Bruce Wayne/Batman character into a grizzled old man who goes back to fighting crime after a years-long hiatus. Along the way, he meets old friends who have fallen from grace, fights Superman in a vicious ideological showdown, and tackles villains who — it turns out –aren’t all that different from Batman himself.

This double whammy showed a whole new generation of comics creators how to do two very important things. The first, with WATCHMEN, was how to create your own universe from scratch and explore deep, complex things in new ways. The second, with TDKR, show how to take classic characters and reimagine them in new ways that could help both new and old readers discover what was right in front of them the whole time.

We’re going to have to skip the ’90s, which I have heard described as the “big guns and big tits” phase of comics. This is a gross oversimplification of a great period in comics, a decade that invigorated a new independent spirit in the industry (with Image Comics) and was a financial boon for the industry. However, I’ll be forced to defend the 1990s later. I need to talk about the prime rib here. Particularly, the years 1999 through (roughly) 2012. This era is so deep and rich and complex it’s hard to know where to begin.

I was a die-hard Marvel fan. Let me just start right there. For that particular publisher, the early 2000s were still a time dominated by the X-Men, a superteam of multicultural heroes known as mutants who are gifted with various powers at birth. At the time, Fox Studios were building the still young X-Men film franchise. This coincided with the NEW X-MEN series by Grant Morrison and a host of artists, including Frank Quitely. It was a superb run with mind-bending twists, a real deep dive into the concept of “mutants”, and defining permutations of the characters that would be used for the majority of the decade.

ASTONISHING X-MEN, the next best run of the X-Men, was written by Joss Whedon and drawn by John Cassaday. And, yes, that’s the same Joss Whedon who would go on to direct MARVEL’S THE AVENGERS (2012) and AVENGERS: AGE OF ULTRON (2015). Whedon and Cassaday’s ASTONISHING X-MEN run was equally phenomenal when compared to NEW X-MEN, despite taking a more traditional take on the characters and embracing the campier sci-fi elements of the team. Nevermind that the “Ultimate” version of the X-Men was being done at the same time, with writer Mark Millar and semi-regular artist Adam Kubert.

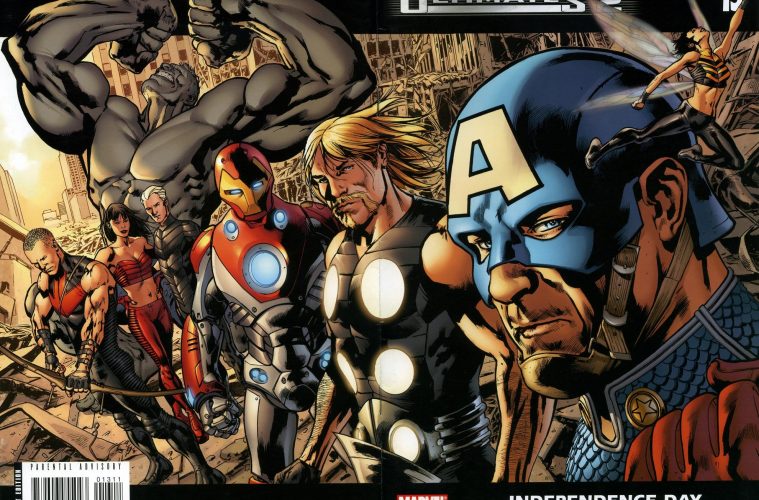

Speaking of the now defunct “Ultimate” line, how important this imprint of reimaginings was to Marvel Comics as a whole can’t be overstated. In its essence, the Ultimate titles were dedicated to updating Marvel staples like Spider-Man, the X-Men, and the Avengers. While this wasn’t unprecedented, it was handled with the same edge that Frank Miller brought to THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS. Chief among these books was THE ULTIMATES, a title dedicated to reinterpreting the Avengers. Written by Mark Millar and penciled by Bryan Hitch, this book took these classic characters, added a thick layer of real-world snark and humor, and combined it with all too relevant themes of a war on terror gone too far — all while the Iraq War was at its peak. Oh, and never mind the amazingly cinematic art from artist Bryan Hitch. Hitch’s visualization of the Avengers went as far as “casting” Samuel L. Jackson as Nick Fury. It was a tongue-in-cheek nod to the aspirations of the book, but life would famously imitate art when Jackson would actually go on to play Nick Fury in future Marvel films. Even further, the comic was critically acclaimed, sold massively, and inspired the same Avengers movies that Whedon would go on to direct.

And Millar wouldn’t stop there. He would then team up with Steve McNiven in the “normal” Marvel universe to create the multi-issue comic event CIVIL WAR. This throwdown split the heroes apart, with various characters joining Captain America on one side or Iron Man on the opposing end. Again, this would go on to inspire CAPTAIN AMERICA: CIVIL WAR (2017). See a pattern here?

Millar was not the only one at the height of his powers during the 2000s. Writer Garth Ennis and artist Steve Dillon rebooted the Punisher in the early 2000s and began one of the greatest character revivals in comics history. Their time on the character would inspire two movies and the current Punisher Netflix show. Almost simultaneously, writer Greg Pak, artists Carlo Pagulayan, and artist Aaron Lopresti would re-energize the Incredible Hulk with PLANET HULK (which, in my opinion, inspired the best part of 2017’s THOR: RAGNAROK), and was then followed by a massive comics event called WORLD WAR HULK. Not to be left out, British writer Warren Ellis was taking multiple swings at Iron Man as well as other characters. Ellis’ EXTREMIS run that was penciled by Adi Granov would also earn legendary status as the inspiration for IRON MAN 3 (2013).

Then we had Brian Michael Bendis, arguably the most prolific Marvel writer of the bunch. His work on ULTIMATE SPIDER-MAN (drawn by Mark Bagley) and DAREDEVIL (drawn by Alex Maleev, among others) were considered definitive takes on those respective characters.

Oh, and nevermind the mind-bending run that J. Michael Straczynski had with artist Gary Frank on SUPREME POWER, or the work he did on AMAZING SPIDER-MAN. Finally, writer Daniel Way was working with artist Steve Dillon on character-defining runs for both Wolverine and Deadpool, the two most popular mutant characters out there!

Now that my Marvel fanboy bias has run it’s course let’s move onto the other great house of graphic art, DC Comics. In all honesty, it’s fair to call this the Grant Morrison era at DC. After doing the aforementioned NEW X-MEN run, Morrison went to Marvel’s competition and was allowed to cut loose. He made the transcendent ALL-STAR SUPERMAN, which took the character back to it’s wholesome, “whizz-bang” roots, reminiscent of the Silver Age. Shortly after, everything Morrison touched involving Batman was a tour de force of awesome. Starting with BATMAN #655, the Scottish writer explored every dark and twisted aspect of the character’s mythos he could. All of this was done with Frank Quietly, Andy Kubert, and a host of other artists.

Right before Morrison began this era, Darwyn Cooke created DC: THE NEW FRONTIER, which single-handedly bridged the tenuous gap between the Golden Age and Silver Age. It’s around this time that Mark Millar shows up again, this time with artists Dave Johnson and Kilian Plunkett to make SUPERMAN: RED SON, a reinvention of Superman that asks, “What if Kal-El’s rocket arrived in the Soviet Union instead of the United States?” This too would be critically acclaimed and go on to softly inspire Henry Cavill’s version of the man of steel in the DC movie-verse.

But it wasn’t just the core string of characters where DC shined bright. Under their separate Vertigo and Wildstorm imprints, all sorts of creators flourished with original stories within their more unrestrained worlds. Brian K. Vaughn was penning Y THE LAST MAN, a story that followed the trails and tribulations of the literal last man on earth. He also created EX MACHINA with Tony Harris, and then PRIDE OF BAGHDAD, a unique tale on the Iraq War from the vantage point of escaped zoo lions. PRIDE OF BAGHDAD the most critically acclaimed graphic novel of 2006. All of this would lead to Vaughn transitioning to working on the show LOST (yes, that LOST) and becoming a producer and writer of television.

Vaughn wasn’t the only talent at Vertigo creating medium defining entertainment. Brian Azzarello and Eduardo Risso started their magnificent run on 100 BULLETS in 1999 and finally finished in 2009. A sprawling, multi-layered, nuevo noir crime epic, 100 BULLETS further helped shift dated perceptions of what types of stories comics could tell.

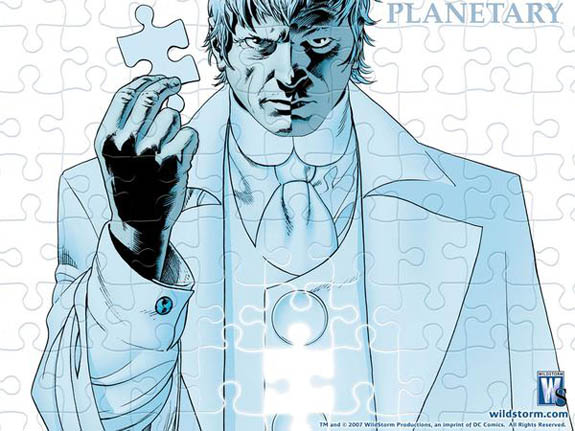

Also starting in the late ’90s into the early 2000s, Warren Ellis gave us THE AUTHORITY with artist Bryan Hitch at Wildstorm. This hardcore comic about a group of heroes called “The Authority” featured what may be the first openly gay mainstream superhero couple, and would inevitably be the epicenter for this new Golden Age of comic books. Not to mention, the Ellis comic PLANETARY with John Cassaday. A love letter to many of Ellis’ pop culture influences, PLANETARY took icons like Godzilla, the Fantastic 4, and Tarzan and turned them all on their heads — making them part of a connected universe of sci-fi adventures. It should also be noted that from Wildstorm came talents like Mark Millar, Frank Quitely, and Bryan Hitch.

Of course, there are more than two comic book publishers. During this time, other houses within the industry were going through a renaissance of their own. Robert Kirkman developed THE WALKING DEAD with Tony Moore. You may have heard of it seeing how it has since spawned two television shows and went on to become a cultural juggernaut in its own right.

Older, established legends were still kicking, too. Alan Moore would have what may be his most prolific period during the early 2000s. He would develop THE LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMAN (art by Kevin O’Neill), which will be concluding its journey at IDW this June. LOEG took classic literary characters and turned them on their head while featuring an openly transgender character in the mix. Right before that, Moore penned TOM STRONG, a comic that freely featured an interracial family that tackled race in a way that many writers would attempt to emulate a generation later.

It must be mentioned that the sheer number of independent comics that were turned into major motion pictures around this period was staggering. Some examples are 30 DAYS OF NIGHT by Steve Niles and Ben Templesmith, WANTED by Mark Millar (again!) and J.G Jones. I also have to include Frank Miller’s 300 (2006) and SIN CITY (2005), both stories created outside of this “New Golden Age” bubble I’ve created but both worth bringing up as each was turned into a “comic book” movie that posted amazing earnings at the box office and trailblazed the way for MARVEL’s own cinematic universe.

This select array of stories from Marvel, DC, their sub-publishers, and independents are just my highlights from this stretch of time. Or, more to the point, Regardless of what you loved from this era, I’d imagine it is hard to argue that — as a whole — the average book then were pretty kick-ass rides that featured jaw-dropping art and boundary-pushing storytelling. More importantly, this era marked the point where comics stopped trying to be for adults and simply owned the fact that it was a space that could be for adults and by adults. An industry where you could create art worthy of intense study and criticism. Sadly, it seems like the comic book industry has been eager to gloss over these years. Why that is, I’ll let you speculate.

This select array of stories from Marvel, DC, their sub-publishers, and independents are just my highlights from this stretch of time. Or, more to the point, Regardless of what you loved from this era, I’d imagine it is hard to argue that — as a whole — the average book then were pretty kick-ass rides that featured jaw-dropping art and boundary-pushing storytelling. More importantly, this era marked the point where comics stopped trying to be for adults and simply owned the fact that it was a space that could be for adults and by adults. An industry where you could create art worthy of intense study and criticism. Sadly, it seems like the comic book industry has been eager to gloss over these years. Why that is, I’ll let you speculate.

Now, here at Action A Go Go, we’ve made it a point to always respect the past, and, truly, the era between the late 1930s and the 1950s is the first Golden Age of comics. We will never argue that fact. But in terms of raw storytelling prowess, artistic greatness, insanity, and sheer genre-defining work…this New Golden Age can’t be ignored. With all of this laid bare, I am going to double down and make an announcement: Henceforth, the era from 1999 to 2012 shall be known as “The New Golden Age” in comics.