In late April, Action A Go Go writer James David Patrick attended the Turner Classic Movies Film Festival. Bullitt, the 1968 Steve McQueen actioner, just happened to be one of the films spotlighted during the multi-day event. Below, Bond_age_’s James David Patrick examines the film’s biggest highlight: The car chase through the streets of San Francisco.

If you know nothing else about the 1968 film Bullitt, you know the film features a landmark car chase by any measure of celluloid worth. The baggage that goes along with that expectation, however, has the potential to become misrepresentative. Historical context helps, such as familiarization with 1968’s practical mechanics and style of filming and editing a car chase. When modern viewers hear the phrase “car chase,” images of The Fast and the Furious and Gone in 60 Seconds flash through their mind’s eye – movies crafted and marketed around the pretense of adrenaline-soaked thrills.

Such contemporary films showcase “the chase” as the main and potentially only attraction. You’re not merely expecting one chase, but dozens of chases strung together. A chain link fence of action beats. Where does one end and another one begin?

Contemporary viewers thus might have a complicated reaction to a film like Bullitt when they learn that the 9 minute and 42-second car chase of legend takes place nearly an hour into the film and doesn’t function as the film’s climax. It wouldn’t take nearly that long to recognize that Bullitt, despite the title and reputation based on an individual scene, isn’t an action film at all, but a riveting police procedural about the seedy politics surrounding witness protection. Slap that pull quote on your movie poster and watch the dollars roll in.

TCM scheduled a Bullitt matinee on the IMAX screen at the 920-seat TCL Chinese Theatre, making it one of the festival centerpieces. Festival marketing featured Steve McQueen’s visage on posters and passholder badges throughout the four-day event.

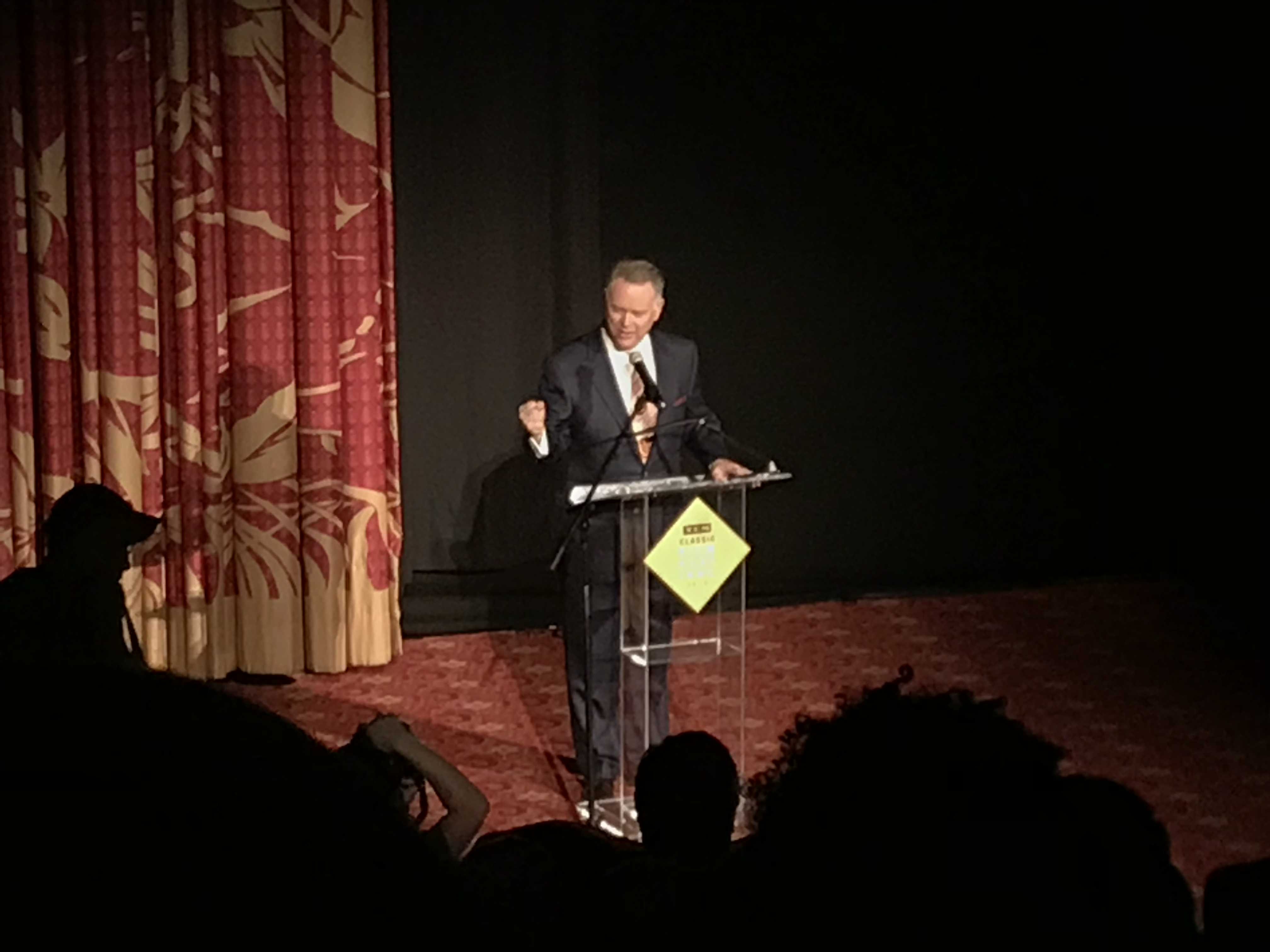

The Czar of Noir, TCM’s Eddie Muller, introduced Bullitt before a nearly packed house. He claimed to have come to proverbial blows with Ben Mankiewicz over who would get the privilege of introducing Steve McQueen’s co-star and guest Jacqueline Bisset. Unfortunately for everyone in attendance (and especially Eddie Muller), Jacqueline Bisset could not attend due to a family emergency. Fighting back his disappointment, Eddie Muller steered the pre-show introduction toward location shooting in his former home of San Francisco, especially as it pertained to the locales used for Bullitt’s car chase.

Collective crowd cheer #1: Eddie Muller’s first mention of “the chase” before the screening of Bullitt at the TCL Chinese Theatre.

Based upon the volume of the crowd’s first woop, the majority of attendees had already seen Bullitt. Eddie Muller prompted the first-timers to make themselves known through a show of applause. It would not be a stretch to suggest that those newcomers had chosen the film for the same reason as everyone else. To see Steve McQueen driving around San Francisco in a Highland Green 1968 Ford Mustang GT fastback with a 390-cubic-inch V-8 on an IMAX screen four-stories tall.

Before continuing, I’d like to make a personal confession. My first experience with Bullitt came in my middle teens and was decidedly lesser than those that arrived at the Chinese Theatre on April 27th, 2018. I rented a Bullitt VHS from Blockbuster Video. I’d like to claim that I found myself in a more enlightened state than viewers expecting nothing but Action McQueen for 100 minutes. Alas, I cannot. I found myself checking the runtime and wondering about the arrival of something – anything – resembling action. Stakeouts and Robert Vaughn’s passive aggression didn’t satisfy. Mercifully, the car chase finally arrived, and even though there are some liberties taken with driving physics to amplify the speed and excitement of the scene, the whole thing felt… sluggish. Less like a car chase of cinematic legend and more like cars driving kind of fast. I, like, other simpleminded children of the music video generation had been reared on rapid editing and stylized action. I shelved Bullitt and all its inaction and I didn’t revisit the film until the release of the Blu-ray in 2007.

I found myself checking the runtime and wondering about the arrival of something – anything – resembling action. Stakeouts and Robert Vaughn’s passive aggression didn’t satisfy. Mercifully, the car chase finally arrived, and even though there are some liberties taken with driving physics to amplify the speed and excitement of the scene, the whole thing felt… sluggish. Less like a car chase of cinematic legend and more like cars driving kind of fast. I, like, other simpleminded children of the music video generation had been reared on rapid editing and stylized action. I shelved Bullitt and all its inaction and I didn’t revisit the film until the release of the Blu-ray in 2007.

Much had changed in the interim, namely perspective and scale. I’ll spare you the personal biography, but it involves things like film school, thousands of movies watched, and the eventual preservation of original aspect ratios. Not to get too deep into the “presentation matters” argument, I’ll just say that the phrase “Formatted to fit your TV” castrates Cinema. Regarding my initial dismissal of the film, I’ll blame the ignorance of youth and the claustrophobic 4:3 cropping of a 1.85:1 film on a 20” television. Comprehending the speed and physical weight of a car chase in two-dimensions requires the establishment of space – the most notable subtraction when a widescreen frame is cropped on both sides.

On this occasion in 2007, I watched Bullitt gloriously free from expectation, free from car chase anticipation and unencumbered by the limitations of 1990 home video presentation. Director Peter Yates builds smoldering tension through multiple layers of opposition. Steve McQueen vs. unknown assassins. Steve McQueen vs. Robert Vaughn’s shady politics. Steve McQueen vs. “the man.” Liquid Cool against the Institution. Steve McQueen isn’t just appearing on screen as an actor in a film. He’s gracing us with his presence. So too is the city of San Francisco – an impressive cityscape that I found nearly omitted from the VHS release.  In order to establish cool of this magnitude, Steve McQueen can’t be in perpetual, frantic motion. To establish cool of this magnitude the cool must exist outside the narrative. It must neither be a reaction to outside forces nor as an inciting characteristic. It must just be. Consider James Bond. When is James Bond at his most debonair? When he’s ordering a drink. That’s not narrative – that’s character at the expense of narrative and forward progress. Frank Bullitt is at his most salient level of cool when he’s gathering a stack of frozen dinners from a corner market. If you can be cool shopping for frozen dinners, you can be cool under any circumstances. As a result of this character building, the McQueen cool oozes over every frame – especially ones where he’s driving Highland Green 1968 Ford Mustang GT fastback.

In order to establish cool of this magnitude, Steve McQueen can’t be in perpetual, frantic motion. To establish cool of this magnitude the cool must exist outside the narrative. It must neither be a reaction to outside forces nor as an inciting characteristic. It must just be. Consider James Bond. When is James Bond at his most debonair? When he’s ordering a drink. That’s not narrative – that’s character at the expense of narrative and forward progress. Frank Bullitt is at his most salient level of cool when he’s gathering a stack of frozen dinners from a corner market. If you can be cool shopping for frozen dinners, you can be cool under any circumstances. As a result of this character building, the McQueen cool oozes over every frame – especially ones where he’s driving Highland Green 1968 Ford Mustang GT fastback.

If a movie does not build characters and narrative, it does not give the chase a reason for existing. Without a narrative reason for existing and without perceived stakes, a car chase is just what I described above when I butchered my Bullitt first-watch; it is machinery moving through vacuous space. A film must earn weight and relevance – and that is why Bullitt’s chase does indeed live up to every objective cinematic measure of excellence. It’s long and thrilling, filled with exceptional stunt driving, but it also relates crucially to the story being told. In other words, if you’re only waiting for the car chase to begin, you’re missing out on everything that makes the pursuit worthwhile.

Back in 2018. Back in the TCL Chinese Theatre. Experiencing a film shown in this venue eliminates outside interference and distraction. We’ve established the McQueen cool and experienced the slow build to climax. Now, Frank Bullitt sits down in the driver’s seat of his Mustang and knows that something is amiss.

Collective crowd cheer #2: Frank Bullitt identifies the threat posed by the sinister duo inside a 1968 Dodge Charger R/T 440. He pauses before inserting his key into the ignition.

The magic of the shared theatrical experience – especially with regard to well-known classic cinema – creates communally amplified anticipation. I’m not going to make the argument that in order to truly appreciate any particular film you must witness it on a big screen. I will claim that witnessing particular films in the dark alongside hundreds of like-minded and invested appreciators offers an experience that cannot be replicated elsewhere and that that experience has the power to transcend the very act of movie-watching itself.

Newcomers may not have been able to predict the car chase before Frank Bullitt even revs his engine, but they surely felt the surge of energy inside the theater. The audience supplied the frothed anticipation, and for the next ten minutes, together we experienced a revolutionary moment in classic film. I’d wager no one left disappointed, whether it was their first time with Bullitt or their twentieth.

Collective crowd cheer #3: The chase concludes as Frank Bullitt skids his car just short of a roadside ditch. His adversaries explode in a fiery ball of exploded gas station.

There’s a natural catharsis that comes along with the anticipation of a film or an individual scene, followed by an ultimate release – especially when it comes to well-known scenes of white-knuckle action. Where’s the build to climax in a movie featuring wall-to-wall action? It takes a certifiable classic to satisfy every time. Stunts are just stunts; experiencing the real thrill of the chase requires investment in the story and characters. The thrill doesn’t even require Steve McQueen and an IMAX screen, but it certainly doesn’t hurt.

Collective crowd cheer #4: Cool wins. The credits roll.

Discover more from James David Patrick’s TCMFF experience. Take a look at his recap of the screening of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (with Melvin Van Peebles in attendance).